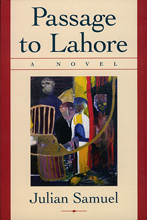

Passage to Lahore, The Mercury Press (1995)

ISBN 1-55128-024-8

“… a few light taps of rain made me turn to the window. Yes, the newspapers were right, the Pakistani chicken pox was all over England. It had moved on the vast oceans along the salty terrorist north coast of Libya, across the Algerian coast where a war was concluding, with the right side winning.”

Passage to Lahore is a no-holds-barred telling of the Pakistani-Canadian-British-Indian-Québecois experience, challenging conventional history with frequent outbreaks of scathing satire. Fractious, erudite, and raunchy, Samuel’s narrative takes us from Montréal to Lahore to Algeria to Hong Kong to China to Surrey, in search of ways to comically damage the suicidal sterility of The Correct and of the tribal debates raging today.

The Mercury Press

22 Prince Rupert Ave.

Toronto, Ontario M6P 2A7

416/531-4338 fax: 416/531-0765

mpress@pathcom.com

Order From Publisher if required: 17.95 dollars including shipping.

Reviews

Reviews and details on Passage to Lahore (French translation: De Lahore a Montréal) by Julian Samuel

PASSAGE TO LAHORE by Julian Samuel

The Mercury Press

22 Prince Rupert Ave.

Toronto, Ontario M6P 2A7

416/531-4338 fax: 416/531-0765

(ISBN 1-55128-024-8)

“Passage to Lahore is a no-holds-barred telling of the Pakistani-Canadian-British-Indian-Québecois experience, challenging conventional history with frequent outbreaks of scathing satire. Fractious, erudite, and raunchy, Samuel’s narrative takes us from Montréal to Lahore to Algeria to Hong Kong to China to Surrey, in search of ways to comically damage the suicidal sterility of The Correct and of the tribal debates raging today.

CONTENTS

- Indonesian Restaurant: Montréal, 1985: 7

- Plague Years in England: Surrey, 1966: 10

- Grandfather at Noon: Lahore, 1957: 16q

- Montréal, 1985: 29

- Frantz Fanon Conference: Algeria, 1987: 44

- Rushdie on the Hooghly River: Calcutta, 1988: 67

- Lipstick on Your Collar: Toronto, 1968: 78

- Of Milk, Mice and Men: Montréal, 1983: 81

- Progressive Sexual Intercourse: Algeria, 1987: 105

- Indonesian Restaurant: Montréal, 1985: 110

- Man of Empire: Toronto, 1989: 119

- Québec and the Communal Question: Montréal, 1985: 133

- Deep Relationships: Montréal, 1989: 145

- The Cannibals of Maarra: Montréal, 1985: 148

- Report of an Officer Who Was Educated in the West: 159

- The Starry Night I Met Begum Akhtar: Lahore, 1984: 160

- Hong Kong and the Boat People PART ONE: Hong Kong, 1989: 185

- Indonesian Restaurant: Montréal, 1985: 200

- Hong Kong and the Boat People PART TWO: Hong Kong, 1989: 207

In French: Les Editions Balzac-Le Griot, Montréal

De Lahore à Montréal

de Julian Samuel

Le Livre:

Récet de l’errance et de l’immigration, Julian Samuel nous entraîne dans ses souvenirs d’enfance et d’adolescence, de Lahore jusq’en Angleterre, puis Toronto, pour aboutir à Montréal, où l’auteur vit désormais. Cette expérience de vie, Julian Samuel ne craint pas de nous la narrer avec l’emportement, les idées et les impairs qui lui sont propres. Julian Samuel irritera certains âmes sensibles, surtout parce qu’il a toupet d’émettre des opinions dont certaines seront très mal reçues, mais ses critiques et le tir groupé de Julian Samuel sont atténués par son sens de l’humour, quelque peu cabotin certes, mais qui se révèle le plus souvent perspicace et sonne juste.

Reviews:

24 May, 1998, published somewhere online.

It is a challenge to review Julian Samuel’s ‘Passage to Lahore’. On the one hand, it is an often brilliant book, jolting the reader with its insights into Pakistani and Canadian (and a few other) societies and often provoking spontaneous laughter by its deft, sardonic prose. On the other hand, it is a bitter piece of work, with dark undertones of anger and deep disappointment. Above all, speaking as one who is not a literary critic, it is a great read, romping incisively across contemporary sociopolitical sites and making savage sense of them and their interconnections.

The book loosely follows its first person narrator, a youngish man of Pakistani Christian background, from Lahore to the UK., and then to Canada; the narrator’s short visits to India, Algeria, and Hong Kong provide a few more transnational vignettes. The subtitle is a “a novel” and a quote on the back calls Samuel a voice “within postcolonial fiction,” but this is an unmistakably personal story and one of its targets is postcolonial and postmodern work of all kinds. Samuel is too familiar with the highly political and pretentious academic world and he savages it unmercifully throughout; I particularly liked his bit about PC sex in Algeria. He is also too familiar with Canada’s multicultural social and political landscape, and his encounters with the bureaucracy which presides over the “opportunities” it offers are furiously comic.

Samuel writes eloquently, positioning himself variously as an informed insider, a marginalized outsider, or both at the same time. His work speaks more clearly and directly about the transnational, postcolonial, postmodern world than most of the work done by people securely positioned within it. Read it and despair.

Karen Leonard, Anthropology, UC Irvine.

*

(SABC) South African Radio

by Hien Marais

A way more authentic outsider is Montreal writer and videomaker JULIAN SAMUEL. In his book – PASSAGE TO LAHORE – he describes himself as a Christian-Pakistani-Quebecois-Montrealer … here’s someone who’s never going to belong. SAMUEL’s book is part novel, part memoir, part travelogue – leap-frogging across history and continents. And it’s driven by the stymied dreams, the ponderous disappointments and, inevitably, the bitterness of an outsider whose politics – in this case they’re Marxist – force him to believe ultimately in HIMSELF. A huge contradiction which SAMUEL, with bile and insight, tracks like prey. Nothing and nobody escapes a kick in the groin – least of all Quebec nationalism and Canada’s hallowed programme of multiculturalism. Whatever your own convictions and sense of history, SAMUEL rubs your nose in it and reveals the stench we learn to ignore. Like SAMUEL’s videos, this book never keeps its distance, it cannot be merely consumed at arms’s length. It stares you down. If you’ve got the heart, this is a must read. That’s Montreal author JULIAN SAMUEL’s “Passage to Lahore”.

*

The Montreal Gazette, 5 July, 1997

Gadfly on our body politic: Despite the barbed invective, Julian Samuel loves Montreal

by Elaine Kalman Naves

A self-defined Marxist Pakistani-British-Canadian Montrealer, Julian Samuel is an author, film-maker and video producer whose work explores real and imaginary borders, the clash of cultures and issues of identity in a post-colonial world. His episodic protest novel, Passage to Lahore, (Mercury Press, 1995), and his other writings needle and provoke the reader by their restless tone and subversive content. But in person (we met at a St. Denis St. café on a balmy day in early spring), Samuel is a bundle of contradictions: accommodating and modest, openly inviting of criticism, then launching himself on a rant on the subject of Quebec nationalism, one of the subjects that most persistently attracts his considerable powers of barbed invective in the novel.

As much a collection of ironic personal essays as a novel in the conventional sense, Passage to Lahore has as its protagonist a character similar in his vital statistics to the author. Both are called Julian, and were born in Lahore, the second largest city in Pakistan, in 1952. Passage to Lahore attacks the racist undercurrents of the places where Samuel has lived since leaving Pakistan in 1958 (England, Scotland, Ontario and Quebec) without for a moment glorifying his native land.

The grandson of a writer of technical drawing textbooks (his grandfather “was sort of James Joyce of the drafting textbook world in post-partition Pakistan,” he writes in the evocative chapter, Grandfather at Noon), Samuel was sensitized to the idea of minority status early in life. Originally of Sikh and Jain background, the family had converted to Christianity and Samuel attended private Catholic English schools in Lahore. “There were all degrees of minoritization in that we were Christians in a Muslim state,” he told me. Whereas Punjabi was the majority language, we were an Urdu-speaking family living in Lahore, which is the capital of Punjab.”

Samuel is loath to ascribe discrimination toward the Christian minority in Lahore as the main reason that his family left. “The first reason would be the ‘American Dream,’ of actually acquiring an affluent, modern lifestyle in the West. And I’m sure that the valid excuse of being a Christian minority in an Islamic state fuelled the desire to leave….And judging by the face of contemporary Pakistan now, it was probably a good idea that we left the homeland because there is frightfully little tolerance for any minority (today).”

Decrying modern Pakistan’s treatment of Hindus, Buddhists, Sikhs, Shi’a Muslims, as well as Christians, Samuel becomes eloquently passionate. “It’s a dream of independence gone all bizarrely wrong, it just seems like a strange irremovable tumour from my life that I can’t get rid of. Here in Quebec again the filthy little word ‘partition’ has cropped up. And it is the most violent word in the English language!”

Despite his frustrations over trying to get funding for his projects in Quebec and his diatribes against what he calls Quebec’s program of “radical provincialism,” when asked about “home,” Samuel categorically states that it is Montreal. “I love this city… it’s a wonderful city. It’s the cheapest city in the world. If you were to live in Calcutta in rupees, it would be more expensive than here….This is a most manageable city, a cosmopolitan city where I live in three languages – Urdu, English and French – every day of my life.”

Anger leavened by humour drives Samuel’s writing. “Anger by itself is cynical and nasty and unproductive. But anger with a sense of humour and sarcasm is a survival strategy. I’d much rather be less angry. But living here in Montreal one has an unlimited supply of fuel to keep one bubbling until well into the middle of the next century. One gets frightfully cynical living here as a minority.”

Samuel is currently at work on both a screenplay and a new novel called The Entanglement (Fatwah). Set in the near future, it’s a comic satire loosely based on the Salman Rushdie affair.

Passage to Lahore has recently been translated into French and is published by Les Editions Balzac.

Elaine Kalman Naves

*

The Montreal Gazette, 9 December, 1995

Master of Tongue-Fu

Restless author wanders from the Main to Pakistan

By Carol M. Davison

In her introduction to Mae West’s recently republished 1930s novel The Constant Sisnner, Kathy Lette describes West as “a black belt in the art of tongue-fu,” a woman capable of “barbecuing entire herds of sacred cows.” On the basis of his recent novel Passage to Lahore, the same abilities should be attributed to Julian Samuel.

A well-travelled, Pakistan-born, Montreal-based film-maker, writer, artist and self-proclaimed “left-intellectual” who never tries of reminding his readers (in a rather nettled a way) that he lives from welfare cheque to arts grant, Samuel is a male version of Camille Paglia.

Although billed as a novel, Passage to Lahore is best classified as a series of poetic, provocative and politically focused travelogue pieces set everywhere from the Montreal Main to a Frantz Fanon conference in Algeria, a roof party in Hong Kong and a small restaurant in Pakistan where the menu reads, “Political discussions and drinking strictly forbidden.”

On the issue of Quebec separatism, Samuel offers several scathingly articulate chapters that expose what he calls the racist undercurrents and farcical manipulations of liberation rhetoric. Here’s a 1985 pronouncement: The Québécois regimes, especially the one in power now, are an allegorical equivalent of many middle-class mimic-Western regimes in Third-World countries: lots of Mercedes parked out in front of renovated houses, little substance, little vision, no courageous debates in the press, lots of technocratic types running the show and doing what can only be called anti-thinking.”

An unusual blend of literary styles — there are some gorgeously sensual passages about Samuel’s childhood and travels alongside a few comic mini-film scripts and a recipe for curried lamb — Passage to Lahore is an often irreverent romp through the immaculate tulip gardens of political correctness, punctuated by exquisite nutshell portraits of the mid-1980’s Montreal scene.

Take this vignette of Park Ave (reviewer means Saint Laurent — js): “This general area, once a more Portuguese neighbourhood, has been transformed into a neighbourhood of artists, humourless ecologists, and women who publish illustrated theories on female ejaculation.”

After all is vilified and undone, however, Samuel manages to barbecue himself, his most sacred cow. His self-portrait, by way of describing a Hong Kong friend, is damming: she loves art, books, visible minorities, animal rights, holidays in the Southern hemisphere, armed liberation movements, save-the-elephant-tusks clubs, kids — all the things that left-wing

intellectuals like me like.” And for someone who insists on the seriousness of racial politics, he constantly undermines the importance of gender politics. Feminists are never taken seriously. They are simply more challenging to bed.

At a guaranteed one guffaw per page, Passage to Lahore is nonetheless a must read for the politically thoughtful. I guess that rules out my idea of sending a copy to Jacques Parizeau for Christmas.

Passage to Lahore, by Julian Samuel (Mercury, 240 pp.,)

*

VOIR, 8-14 may 1997

De Lahore à Montréal

de Julian Samuel

Ed. Balzac, 1997, 253 pages

Robert Beauchemin

Ah!, le cinglant ouvrage! Voilà une sorte de roman-essai, écrit parfois à la hâte, qui emporte tout sur son passage, pêle-mêle: le nationalisme québécois, le Canada, l’altérité, l’art, la critique, Robert Lepage et Denys Arcand, les femmes aussi bien que les juifs, les Arabes et les homos. Non, on ne peut pas rester insensible au roman de Julian Samuel: De Lahore à Montréal.

Pakistanais de naissance, l’auteur a immigré dans l’Angleterre pré-thatchérienne à l’adolescence, pour aboutir enfin dans le Montréal pré et post-référendaire; pas exactement le genre de trajectoire dont on ferait une vie sans histoire. On pense tout de suite au Salman Rushdie des Patries imaginaires (1994), un livre inclassable rempli d’anecdotes, de récits et de commentaires politiques, littéraires et sociaux, que l’écrivain avait publié en 1991. Ce livre hanté par le sentiment de la perte de l’appartenance parlait aussi d’errance. Mais là s’arrête toute comparaison. Rushdie se considère d’abord comme un écrivain et se trouve aux antipodes de Samuel, un touche-à-tout à la fois philosophe, photographe et cinéaste.

Et en ce sens, la réflexion de Julian Samuel fait penser aux carnets de voyage post-modernes, ces collages docu-fiction si chers aux Américans. S’y trouve une suite d’anecdotes sans direction aucune où l’auteur, par son désir — voire son obsession – de faire “sérieux” et d’éviter une narration linéaire, prend position sur tous les sujets de l’heure, en passant d’une époque et d’un sujet à un autre sans ordre chronologique, en parfait savant du coq-à-l’âne. Ainsi passe-t-on de Montréal en 85 à Hong-Kong en 89, à Lahore en 84, puis à Alger en 87, allant des Palestiniens à la rudesse de l’hiver montréalais, à un avis sur les écologistes et sur le PQ dont les “leaders ont l’air de protonazis”. Il réussit même à nous donner une recette de curry d’agneau.

S’il y a quelques bons moments, ceux par exemple où Samuel, au demeurant bon conteur, retrace sa vie d’étudiant et ses conversations avec des colocataires utopistes, ou encore de savoureux passages avec son oncle ou son copain homo séropositif, il ne peut s’empêcher d’entrecouper son récit de fragments idéologiques et didactiques, de clichés d’une infinie platitude du genre “postcolonial” et “luttes des classes”, qui se comparent aisément aux pires cours de science po 101. Déconcertant.

Que l’auteur fût marxiste avoué, soit. Qu’il s’inscrive volontairement ou non dans la littérature de l’engagement, on ne peut l’en blâmer. Et qu’il veuille faire une oeuvre choc sur la bêtise et l’ethnocentrisme, le but est louable. Mais ce que le lecteur retiendra surtout, c’est le mépris total du patriotisme québécois que Samuel compare à un virus et qui, par des propos incendiaires, cache à peine son mépris pour les francophones. Le Québec “a attrapé une sorte de micronationalisme, la pire de toutes les maladies”.

À travers des raccourcis parfois téméraires, qui témoignent d’un manque de rigueur, et dans une langue inutilement corrosive, l’auteur attaque sans cesse sa nouvelle patrie où, dit-il, “la vie est impossible”. Avec des passages comme “parler français ne m’est d’aucune utilité”, ou encore “je me souciais comme d’une guigne d’être admis dans un Québec pluraliste”, ou encore “le Québec est une colonie dépourvue de métropole, la périphérie de la périphérie de la périphérie”, Samuel fait montre d’une intransigeance futile.

Il y a quelque chose de belliqueux et de déplaisant dans ce livre. Puisant dans ses souvenirs, Samuel semble incapable de surmonter sa rage dans une oeuvre où transparaissent des blessures profondes, maladroitement exprimées. Tout en ayant souffert de l’injustice, il ne se gêne pas pour être vulgaire et provocateur. Cela sert-il vraiment son propos? On peut certes sympathiser avec la cause, mais difficilement avec ce livre, qui m’est presque tombé des mains, et pas seulement par ennui.

*

Response from Julian Samuel — published

Julian J. Samuel

8 May, 1997

VOIR — Courrier des lecteurs

Je veux vous remercier pour la critique de mon livre

De Lahore à Montréal [Voir, 8-14 Mai, 1997]. Mais je suis certain que si je n’avais pas appelé Richard Martineau un million de fois, mon roman serait resté dans les poubelles réservées aux intellectuels “immigrants.”

Martineau, rédacteur en chef de VOIR n’est pas raciste. Pas pour une

seconde. Mais hormi quelques trop rares exceptions, son hebdomadaire ne fait que promouvoir sa propre tribu: blanche, Québécoise et francophone. Le Devoir fait la même chose, avec en prime une directrice qui se sert du DEVOIR pour faire sa propre promotion: Lise Bissonnette, reine du permafrost a monopolisé la première page du cahier “livres” du Devoir en 22-23 mars 97.

Voyez comme VOIR vend le journaliste Paul Marchand (un Français) qui n’a écrit qu’un livre plein de clichés en comparaison avec Heart of Darkness (1902) de Joseph Conrad. Voyez comme VOIR encourage le travail ultra-superficiel de Robert Lepage, plouc ‘toutte chromé.’

Comment expliquer autrement que par ce tribalisme, le fait que je n’ai droit qu’à une seule petite critique bien qu’élégante, signée Robert Beauchemin – alors que cela fait 18 ans que je travaille à Montréal. Cela m’apparait injuste. Voici un échantillon de mes efforts: un documentaire de quatre heures sur l’Orientalisme; plusieurs films et video – deux achetés par La Galerie nationale du Canada – un livre de poésie, un roman (Passage to Lahore); et deux livres sur mes films publiés par Black Rose Books.

VOIR favorise les intellectuels qui ont produit, au niveau de la qualité et de la quantité, moins que moi. VOIR les promouvoit parce qu’ils appartiennent à la tribu. Ce qui me force à rester un “immigrant” à Montréal. Un immigrant qui ne pense qu’à vomir sur le visage du chauvinisme Parizeauesque. “Immigrant” après avoir passé 31 ans au Canada?

Julian J. Samuel

*

Le Devoir 21/22 June, 1997

L’orangisme déguisé en esprit frondeur

Un vidéaste-écrivain dénonce les Québécois pour leur nationalisme

De Lahore à Montréal

par Robert Chartrand

Fragments autobiographiques, réflexions sur des problèmes actuels- le sida, la situation des femmes dans les pays islamiques, l’émigration, le racisme-, boutades sur le Québec et son nationalisme: il y a de tout cela, en vrac, dans ce livre juste assez irritant pour ne pas être tout à fait ennuyeux.

Julian Samuel est vidéaste de métier. Né à Lahore, au Pakistan, en 1952, dans une famille musulmane convertie au christianisme, il a émigré en Angleterre d’abord, puis au Canada, où il vit depuis une vingtaine d’années.

La plupart des dix-neuf chapitres -chacun pourrait être une séquence de film-outre leur titre, portent la mention d’un lieu -Montréal, Hong Kong, Lahore, l’Algérie- et d’une année -de 1983 à 1989. Voilà pour les coordonnées spatio-temporelles du livre.

De Lahore et du Pakistan en général, nous apprendrons peu de choses; quelques souvenirs d’enfance, le portrait d’un grand-père qui était un dessinateur industriel réputé, les souvenirs d’un oncle affabulateur. Même chose pour l’Angleterre: le jeune écolier Samuel s’y est, pour l’essentiel, bagarré avec des camarades intolérants. A Hong Kong, il est reçu par des amis fortunés qui s’occupent des questions de réfugiés. En Algérie, il assiste à une conférence à la mémoire de Franz Fanon, l’auteur célèbre des Damnés de la terre qui fut, dans les années 60, le livre de référence de tous les partisans de la décolonisation. Samuel avait réalisé un vidéo-“pas très réussi”, reconnait-il- à partir du livre.

Près de la moitié des chapitres de ce récit au ton volontiers provocateur sont censés avoir Montréal pour cadre; on y trouve des conversations avec deux amis homosexuels dont l’un se meurt du sida; les démêlés de l’auteur avec des fonctionnaires de l’aide sociale à qui il aimerait bien casser la figure; ses démarches en vue d’obtenir une subvention pour un projet de film: au passage il écorche le cinéaste Denys Arcand, dont Le Déclin de l’empire américain est décrété “fastidieux” alors que Jésus de Montréal ne serait “que la pâle travail d’un illustrateur”… Selon Samuel, le Québec, par son cinema, ressemblerait à un pays du Tiers-Monde dans leur “phase d’arrogance-post-indépendance-marquée-d’excès-révolutionnaires”; comprenne qui pourra à cet amalgame.

On s’en doute, l’auteur n’aime pas beaucoup le Québec francophone -qu’il semble d’ailleurs connaître fort mal-, ni son gouvernement, ni ses institutions. Ce pauvre Québec “a attrapé en 1976 une sorte de micro-nationalisme, la pire de toutes les maladies”, encore que Samuel l’estime moins virulente ici qu’ailleurs. Il reste que les nationalistes québécois sont “machiavéliques”; et puis, “leur nationalisme est absolument fermé aux immigrants et aux non-Blancs”. La preuve (scie bien connue): la crise d’Oka de 1990 a bien “démontré cette tendance proto-fasciste des Québécois”; parmi ces rengaines où l’ignorance le dispute à la mauvaise foi -Samuel affirme que la loi 101 interdit tout affichage en anglais-, on trouve soudain ce reproche ultime adressé au nationalisme québécois: “Il ne s’agit en aucune façon d’un mouvement de libération.” Le FLQ aurait-il été plus acceptable selon lui? Il n’en pipe mot.

QUAND L’AUTEUR S’EFFACE

Deux chapitres, où l’auteur-narrateur a la bonne idée de s’effacer, tranchent nettement sur ces facéties; l’un à la fois touchant et dramatique, qui décrit la violence conjuguale chez un couple d’immigrants pakistanais; l’autre très court, qui est le témoignage atroce des supplices qu’un militaire a fait subir à sa victime.

Ceci dit, plusieurs de ces petits récits sont rondement menés; les dialogues sont enlevés et on peut aimet la façon dont Samuel mélange efficacement réalité et fantasmes. Le vidéaste, manifestement, a des dispositions de scénariste. Les gros mots et les allusions à la scatologie pourront -sait-on jamais?- en amuser certains. Hélas! Le propos, lui, est navrant. Les amalgames faciles, les raccourcis de l’esprit qui se donnent l’allure de réflexions “brillantes” sur la vie ne valent pas tripette. Quant aux citations hétéroclites et aux formules-chocs, elles rappellent ces fameux one-liners dont le cinéma et la télévision américains se sont fait une spécialité; version branchée des slogans publicitaires, ils se veulent accrocheurs, amusants, ils paraissent futés et on espère surtout qu’ils vont rapporter gros.

Dans une postface finaude, qui se présente comme un procès de l’entreprise de l’auteur, Michael Neumann lui rend hommage; car si Samuel et son oeuvre ont de vilains défauts, De Lahore à Montréal tenterait bravement de réconcilier fierté, moralité et franchise.

Que retenir de ce petit livre si ce n’est ceci: sottement, à la suite de tant d’autres- on songe aux énormités de Howard Galganov et de Mordecai Richler sur le Québec-, Julian Samuel perpétue ici, sous couvert de cynisme libertaire, cette “obssession ethnique” dont Guy Bouthilier, dans un livre récent qui porte ce titre, a fait l’historique irréfutable. L’orangisme viscéral de certains milieux anglophones qui nous décrétait naguère inférieurs est toujours vivace; pris en charge par d’autres voix, il nous voit désormais racistes, fascistes, intolérants. Que faire, pauvres de nous? Sans doute notre tricot collectif est-il si serré qu’il nous empêche de répliquer…

*

The Gazette, July, 1997

Hungry Mind Review, December, 1995

An Independent Book Review

Passage to Lahore

By Julian Samuel

The Mercury Press

232 pages

Julian Samuel, a Canadian documentary film-maker, originally from Pakistan, has written a novel that seems more like a memoir. The first person narrator is named Julian, and seemingly shares all the author’s biography as given on the book jacket and in the acknowledgments. Julian, the fictional persona, takes us on a bohemian tour; we meet all sorts of engaging characters, mostly Third World immigrants in Canada. When Mr. Samuel describes the characters, rather than Julian’s self-obsessions, the book reminds me of Down and Out in Paris and London. In parts it’s even more engaging than Orwell’s book–less puritanical with its street language, raunchy descriptions, and even explicit sex.p

Julian treats us to his witty, incisive analyses of Canadian, American, and British racism. However, he is not a priest of political correctness; he describes multicultural fashions at North American universities as “visionless, inane, careerist, postmodernist prattle.” Talking about a department head who tries to appear politically correct, he says, “He makes his ugly-tasting white-man’s curries.”

Julian puts down Westerners who try to analyze Asian cultures, like Gunter Grass, whose articles on Calcutta “read like that of one of those

short-sighted Western thinkers, a little like V. S. Naipaul, who did not do much to educate themselves on the real reasons for the ravage of this city and this part of the world.” Julian has the impression that he is enlightened to analyze the West, the East, and anything under the sun, while he castigates most other people’s–especially Westerners’–attempting to do likewise.

Julian’s wit depends on the mastery of the put-down. Describing a Montreal neighborhood, he says, “This general area . . . has been transformed into a neighborhood of artists, humorless ecologists, and women who publish illustrated theories of female ejaculation.”

Julian has strong opinions. For example: “Of course one could write tons of books on narrow-minded nationalisms, but they do not deserve the exposure.” Considering what has been happening in Bosnia, it’s easy to disagree. If more people had understood the narrow-minded nationalisms in these regions, a lot of bloodshed might been prevented.

Julian occasionally compensates for his haughty tone by making fun of himself and his “dull life as a grant seeker in the second largest bilingual city in the world.” However, he does not remain self-critical for long. His failure to get enough grants is another proof of how dull and narrow Canada is. This is how he reacts to a rejection: “She refused my project, accepted the curry recipe, and accepted the mild criticism of her culture with its redundant films on the sex lives of a few narrow-minded professors, their wives, and homophobic assholes.”

The repetitive travelogues–Montreal, England, Lahore, Algeria, Calcutta, etc.–that comprise the book’s chapters are not well connected. The main character does not have a coherent project to give unity to these chapters. And the raunchy aspect gets old: by the end of nearly every chapter, Julian abandons his post-colonial struggles in order to chase women. Despite many excellent anecdotes and brilliant moments, the novel bogs down in too many scenes, scatological details, and secondary characters rendered in the loose fashion of a travel journal.p

–Josip Novakovich

*

Cover story HOUR

Pulling no punches

Filmmaker – and now novelist – Julian Samuel fights his own political battles.

PHOTO CREDIT: THOMAS KÖNIGSTHAL

Martin Siberok

Julian Samuel is a cagey fellow. It’s hard pinning the man down. With his ability to sculpt words into unique verbal creations, the articulate and well-spoken Samuel can tie you up in knots in no time.

Engaging and opinionated, pretentious and humble, the 43-year-old Montreal filmmaker is a colourful character who has terrorized cafés and bars along The Main for nearly 15 years. Mention his name and people either cringe or smile – depending on the reaction his barbed charm has elicited in them.

Interviewing Samuel is like being in a graduate seminar discussing the epistomological importance of race in the class struggle during the latter half of the 20th century. Yet, beneath the seriousness of debate – exacted with the proper inflection – there is no lack of humour in this man’s deconstruction of post-modern society.

A maker of political documentaries – film and video – Samuel has just released his first novel, Passage to Lahore (Mercury Press). The genesis of the book dates back to 1987 when he returned home from Algeria after attending a conference on Frantz Fanon, the Martinique-born doctor whose revolutionary books, Black Skin, White Masks and The Wretched of the Earth, were mainstays for understanding liberation struggles around the world.

“The book loomed up out of this one letter I wrote to an Algerian friend from my university days who now lives in France. It was a report to her about my 10 days in Algeria.

“The combination of that letter with two short stories that I wrote later [previously published in Matrix magazine] became the basis for this book that takes the form of a made-up autobiography, with some things near the truth and others simply flagrant lies – in other words, fiction.”

Samuel expresses no great artistic design behind his venture into the written word or why he chose the fictionalized autobiography as his approach. “It was just something to do to rationalize my existence,” he states bluntly. “Look, there are no sincere motivations behind writing such a book. It’s not a tremendous protest novel, though it might look like one.

“If you want sincerity in my work, then you have to go to my documentaries. Those are a sincere, concrete look at how the West has constructed the Orient in its intellectual history. The book is basically a caustic look at minority individuals in Western society – done with a sense of humour.”

A fractured reality

Taking its name from E.M. Forster’s famed novel, A Passage to India, Samuel’s Passage to Lahore is far from a conventional novel with a traditional protagonist and a linear narrative. Instead, it’s a collection of essays presented in a splintered narrative; an imagistic collage of poignant experiences that possess universality.

“It’s very different from a novel that Hanif Kureishi (My Beautiful Laundrette, Sammy and Rosie Get Laid) would write. It’s a fractured narrative that states a chronology in a desultory form.

“It’s sectioned off in many historical parts but comes together as a whole. You can start and finish anywhere in the novel without it being too discontinuous an experience.”

Suddenly, there’s an abrupt break in Samuel’s narrative. “I find it difficult to talk about the book,” he confesses, lowering his voice. “I’m much more at home in my natural medium, which is film and video. I’m not at home with this medium at all.

“Maybe it’s a little too close to my personal affairs. It’s just been published, and I really haven’t come to terms with it at all. I even have nightmares about it.”

And then, without warning, the sober Samuel returns and proclaims “All the names, sexes, and dates have been changed and manipulated so no one will be able to take me to court.”

First and foremost, Samuel considers himself a filmmaker. “Writing a novel was an arduous struggle. I literally had to teach myself how to tell a story. The person who helped me with this was Sean Kane, my professor friend from Trent who taught me Chaucer and Spencer. He took me through modern critical theory and English literature. He showed me how to propel a narrative – how to put tensions in there that would enable people to flip pages.”

Besides being the personal journey of one person, the multilayered novel touches on a slew of issues including colonialism, nationalism, migration, racism, and AIDS. Plus, Samuel has integrated topics that have occupied him intellectually and politically over the years: the Paris Commune of 1871, the Palestinian struggle for a nation, the 1947 partition of India, Canadian multiculturalism, the Algerian war of liberation, and Canada’s involvement in the international arms industry.

“Surely this is not a book of the excavated experience. It’s a fucking political indictment in many ways. This is what Montreal did, this is how minorities are treated. It is not simply a story of one man’s complaint. In a way, it’s a documentary that takes you around the world to Pakistan, Algeria, Britain, Canada, and ends in Hong Kong.”

Westward bound

Samuel’s own life reflects the patterns of post-colonial migration to the Western world. Born in 1952 in Lahore, Pakistan, Samuel grew up in a middle-class Christian milieu; his grandparents were originally Sikhs and Jains who were converted to Christianity by American missionaries. In 1958, his family left the subcontinent and set sail for metropolitan Britain in hope of a better life. After eight years in the grey, curry-unfriendly Britain, the family crossed the Atlantic in 1966 and settled in Toronto.

In the 70s, Samuel moved to Peterborough and attended Trent University where he received his BA in English literature. In 1979, he moved to Montreal, and completed an MFA in photography at Concordia University.

During the 80s, Samuel underwent a radicalization as he struggled as an artist trying to survive on Canada Council grants and welfare. His anger found a more politicized forum as he exchanged his “bourgeois” art for the agit-prop of filmmaking.

His radicalization was further heightened living as a “visible minority” in politically charged Quebec. When it comes to Quebec’s national aspirations, Samuel pulls no punches. “What is the nationalistic thrust here? Is it race nationalism? It is a projet société like they try to tell us?

“I, in fact, respect Parizeau for saying the truth the other week. He said the Yes side lost because of big money and the ethnics. What’s wrong about saying the truth? Why should sensitive black people get their feelings hurt? Can’t things be faced? It was the ethnic vote that thwarted an attempt at pseudo liberation on the part of the Quebec businessmen.

“But more importantly, what we got was the tip of the iceberg. Maybe within the Parti Québécois there is a reflection of Jean-Marie Le Pen. Why aren’t we [the ethnics] more represented in the party? Is it because there is no space? Is there an indirect edict of expulsion that’s been issued with what Parizeau said?

“These are the fundamental questions you have to ask yourself instead of feeling hurt and dejected.”

Flipping le page

“I have particular problems fitting into Quebec. National culture has to produce artists who are internationally recognized, and those artists who are have to compliment national culture. Robert Lepage is a rather shallow, insignificant artist without any real moral, tactical questions in his mind. I saw his film, Le confessional – it’s this narcissistic look at his own society. I haven’t done this. I’ve taken a look at as many places in the world as possible, and this doesn’t fit into a nationalistic agenda. Hence I am out. Hence I have to struggle really hard to get budgets for my films.

“Look, my book was published in Stratford, Ontario – not Quebec. Why? Because I’m not a promoter of national causes; I’m a critic of national causes.”

In his role as a socio-political critic, Samuel makes statements that are perceived as outrageous and arrogant. “Who says I’m arrogant? I’m not arrogant. Just because I refute conventional wisdom does not an arrogant person make.

“Arrogance is something completely vicious and unproductive. You can’t make that claim about me, I have been productive and I’m not vicious. All I do is mirror back the violence that’s been imposed on me. I’m simply holding up a mirror and saying take a good look.

“I try not to be safe. And here, I use that tired cliché that to laugh in the face of the enemy is the biggest damage you can do.”

For the past 16 years, Samuel has lived in Montreal – a culturally vibrant city with cheap rent. “This city lives and breathes two major languages, no other North American city does this,” explains Samuel. “Montreal internationalizes people in a way Toronto couldn’t, simply because we have two major cultures here. Toronto is multiracial; we are more cosmopolitan. It’s a culturally profitable place for us.”

Then, as is his habit, Samuel pauses for a split second before thoughtfully admitting, with smiling eyes, “I’m very skeptical about some of the things that come out of my mouth.”

Passage to Lahore is available at bookstores around town.

His trilogy: The Raft of the Medusa, Into the European Mirror, and City of the Dead at Cinéma Parallèle Nov. 13, 14, 15

*

The Toronto Review of Contemporary writing abroad

Vol. 16, No2, 1998

Passage to Lahore by Julian Samuel

reviewed by Scott Gordon

“Manic Immediacy”

Like a number of other so-called postcolonial text, it is politics in various forms—in this case usually aggressive and activist in nature—that are at the forefront of Julian Samuel’s Passage to Lahore. The politics of Partition in Pakistan, of separation in Montreal, of race in Enoch Powell’s London, of AIDS in Canada, of revolution in Algeria and of Vietnamese refugees in Hong Kong all find their way into Samuel’s “novel.” It should be pointed out that this is really only a novel in the name and bears none, if any, of the characteristics one normally associates with the genre or even its radical fringe. More precisely Passage to Lahore is a notebook of autobiographical observations and musings on various recurring themes: Marxism, armed revolution, AIDS, sex, the arts in Canada and the South Asian diaspora, among others. A lunch with some HIV-positive friends at an Indonesian restaurant in Montreal in 1985 sits at the core of the book with other entries in the notebook ranging from romantic sketches of his childhood in Pakistan to portraits of the harsh realities of being an immigrant in London and Montreal to the harsher realities of Fanon’s Algeria. At times, possibly in an attempt to capture the diasporic experience more accurately, the book also reads like a travel journal as he remembers his many homes (Lahore, London, Peterborough, Montreal) as well as his various trips abroad (Pakistan, England, Algeria, Hong Kong) to visit friends and family and to attend conferences.

Much like Ruben Martinez in “The Other Side” (Vintage, 1992), Samuel makes use of a number of different literary techniques and styles in order to tell his story: excerpts from newspapers and books of academic theory, bits of poetry, snippets of screenplays and recipes all punctuate Samuel’s notebook. As with Marinez, this cut-and-paste method gives the political and social issues that concern Samuel a kind of manic immediacy and at times a depth that would not be possible in a more conventional treatment. Here politics and the culture that it influences is at once theoretical and anecdotal, real and abstract as Samuel attempts to bridge the gap between the realities of day-to-day life (whether it be an immigrant in Montreal or as Pakistani Prodigal Son returning home for a visit) and the academic posturing of cultural studies departments that study and probe this life in order to give it some kind of deeper meaning.

The major difficulty with this book lies precisely in this tension between the practical and the theoretical. Samuel does not hide his frustration with academia and the hypocrisy he sees at the heart of cultural studies, and yet he has adopted so much of their jargon that it is difficult to know where he really stands and what kind of statement, if any, he is trying to make. And there times when Passage to Lahore drops names rather than use ideas in order to make their point:

“Their ideas are not much to beat down anyway: neo‑Althusserians at best, mixed in with the borrowed language of people from the earth‑shattering Frankfurt School. Poor Walter Benjamin. Some of these intellectuals have kissed the French thinkers goodbye. The very best of them employ Edward Said’s mechanical critiques of Orientalism…” (37)

To give him the benefit of the doubt, it may be irony that Samuel is after rather than any kind of pretentious lesson in cultural theory. Indeed, at times he clearly does not want to be taken seriously. After vacuuming up a mouse that his trap has maimed but not killed, for instance, he writes: “The screeching mouse zipped past my eardrum into the post‑colonial world of dust and asphyxiation.” (85) Or, on another occasion, when day-dreaming about a woman he meets in Lahore he imagines himself saying: “You wanna marry me and live in the hip Plateau Mont Royal area of Montréal, make feminist‑semiotic curries and play post‑colonial exiles?” (166)

These blatant send-ups of academic speak, however, are relatively few and far between and more often than not it seems as though when Samuel is being ironic, it is an irony very unsure of itself and as a result unable completely to let the reader in on its humour.

“It would be unfair to expect them to understand my struggle for a visionary post‑coloniality imbricated with an avant‑garde anti‑Eurocentric projection in the overall rejection of traditional theories of perspectival representation.” (183)

Out of context it is difficult to imagine that such an awkward sentence is meant to be anything but humorous. As part of the narrative, however, one gets the distinct impression that Samuel actually means just what he says. Part of the problem in interpreting this narrative voice lies in the complete lack of character development: we know what books he has read and which schools of thought have had an impact upon his own thinking, but this is not enough to know whether he is being serious or satirical. In the end, even if this irony at its most complex and sophisticated, too many passages like these (and there are many) make for muddled prose which in turn makes for a very unengaging read.

There are times when Samuel’s book hints at what could have been a much more interesting project. As someone from Pakistan, a country created through an act of partition, the perspective Samuel brings to the debate surrounding Quebec independence is both fascinating and important. In one chapter he writes of a discussion between himself and a bureaucrat in charge of assessing a funding grant for his next film (Samuel is a documentary film-maker as well as a writer). His Marxist point of view, his thorough knowledge of the Algerian revolution and his experience as a minority in Quebec all enter into the discussion in a way that is thought provoking and not all pretentious. Had Samuel brought the same clarity of thought and language to the book’s other themes, Passage to Lahore would be more than just a collection of unfocussed opinion pieces in the guise of fiction. Passage to Lahore had the potential of being a very effective alternative to more mainstream middle-class treatments of similar issues, like the recent “Bunties and Pinkies” (a collection of Ashok Chandwani’s columns from the Montreal Gazette, 1996), but instead it has relegated itself to wandering aimlessly beyond the fringe.

*

Compte rendu

« Un réquisitoire haineux » Ouvrage recensé :

Julian Samuel, De Lahore à Montréal, traduit de l’anglais par Jocelyne Doray, Montréal, Balzac, 1996, 256 p.

par Francine Bordeleau Lettres québécoises : la revue de l’actualité littéraire, n° 88, 1997, p. 14.

Pour citer la version numérique de ce compte rendu, utiliser l’adresse suivante :

http://id.erudit.org/iderudit/39271ac

Note: les règles d’écriture des références bibliographiques peuvent varier selon les différents domaines du savoir.

Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d’auteur. L’utilisation des services d’Érudit (y compris la reproduction) est assujettie à sa politique d’utilisation que vous pouvez consulter à l’URI http://www.erudit.org/documentation/eruditPolitiqueUtilisation.pdf

Érudit est un consortium interuniversitaire sans but lucratif composé de l’Université de Montréal, l’Université Laval et l’Université du Québec à Montréal. Il a pour mission la promotion et la valorisation de la recherche. Érudit offre des services d’édition numérique de documents scientifiques depuis 1998. Pour communiquer avec les responsables d’Érudit : erudit@umontreal.ca

Document téléchargé le 15 October 2010 01:09

14

Julian Samuel, De Lahore à Montréal, traduit de l’anglais par Jocelyne Doray, Montréal, Balzac, 1996, 256 p., 24,95 $.

Un réquisitoire haineux

ROMAN Francine Bordeleau

Déformation des faits, malhonnêteté intellectuelle, insultes grossières caractérisent cet énième pamphlet anti-Québec.

Dm DE LAHORE À MONTRÉAL, un « roman » autobiographique publié en anglais en 1995 (pour le référendum, sans doute), on lira entre autres gentillesses que le Québec, dont « la structure

officielle n’est pas très favorable aux immigrants et aux autochtones », « se compose d’une “tribu” blanche et dominante, résidu historique d’une France janséniste et prérévolutionnaire […] ». Ou que les Québécois « peuvent à peine garder la tête hors du marécage idéologique créé par le Parti québécois et ses manœuvres de manipula- tion : l’illusion-de-la-menace-contre-la-langue-française et le désir d’un Québec hors du giron fédéral ».

Qui est ce nouvel émule de Galganov et de Richler ? Il est né au Pakistan en 1952, cinq ans après la partition de l’Empire des Indes ; sa famille émigré en Angleterre dans les années soixante, mais s’installe rapidement à Toronto. Samuel, qui se dit « d’obédience néo-marxiste », est bientôt séduit par les théories révolutionnaires de Frantz Fanon, l’au- teur de Peau noire, masques blancs et des Damnés de la Terre, et se découvre « une attirance “vampirique” pour l’Organisation de Ubéra- tion de la Palestine ». Devenu réalisateur de films documentaires, il quitte Totonto pour Montréal au milieu des années quatre-vingt et enseigne aujourd’hui à l’université Concordia. Au moyen de plusieurs courts textes, De Lahore à Montréal récapitule ce parcours et illustre les idées politiques de l’auteur-narrateur.

Nationalisme, colonialisme, racisme, immigration constituent les grands thèmes du livre, et à l’aune desquels est évalué le Canada, qui apparaît, sous la plume de Samuel, comme un pays sans Histoire et sans culture peuplé de péquenots insignifiants, racistes et tarés. Mais c’est surtout contre le Québec que l’auteur déploie des trésors de hargne, de mauvaise foi et de malhonnêteté intellectuelle. Contre le Québec et, plus encore, contre le nationalisme québécois, dont il se montre bien inca- pable de cerner les enjeux et de situer la genèse. Selon lui, du reste, tous les nationalismes semblent justifiables, sauf celui des Québécois.

Samuel fustige la loi 101, en vertu de laquelle « le français est la langue officielle de notre province. Il est illégal pour un commerce d’af- ficher dans une autre langue que le français. » De toute évidence, l’au- teur n’a pas lu le texte de la loi et n’a pas jugé bon, non plus, de vérifier ses dires — que démentit une simple balade dans Montréal — auprès de l’Office de la langue française. L’organisme lui aurait expliqué que, en matière d’affichage commercial, le français doit être prépondérant, ce qui n’empêche pas d’afficher en même temps dans une autre langue.

Mais il y a pire dans ce livre où transparaît continûment une haine vis- cérale du Québec francophone, et qui n’est rien moins que raciste. L’auteur a décidé de décrire — ou plutôt d’interpréter très subjectivement —, dans le plus beau jargon tiers-mondiste, la crise d’Oka : les « événe- ments dans la réserve indienne ont démontré cette tendance protofasciste des Québécois », affirme-t-il. Suit un résumé très éloigné des faits. En outre, Samuel prendra bien garde de préciser que le seul mort, dans toute l’affaire,aétéunpohcierblanc.Onapprendraparcontreque,

craignant une attaque combinée de l’armée canadienne et delà Sûreté du Québec, plusieurs Mohawks ont pris la fuite en ne laissant sur place que quelques Warriors peu armés.

Non, mais de qui se moque-t-on ? Les armes, on le sait, entraient à Oka par containers, et les Warriors — des mercenaires qui sefichaientpas mal des droits ancestraux des autochtones, un détail qui semble avoir échappé à Samuel —, en réalité armés jusqu’aux dents, ne craignaient sûrement pas « la culture dominante ». Bref Samuel s’adonne ici et tout au long de son Uvre, à une désinformation éhontée, et pratique ainsi sans vergogne ce qu’U reproche aux médias « bourgeois ».

Soyons juste : l’auteur a d’autres cibles. Les féministes, par exemple. Ou Salman Rushdie. Les Versets sataniques ? « De lafictiondestinée à garnir son compte en banque», dira un personnage non identifié. Mais Rushdie, victime d’une fatwa lancée par Khomeiny, s’est également attiré les foudres des fondamentaUstes pakistanais. Et tout laisse croire que Samuel est un intégriste qui s’avance masqué.

On en prendra notamment pour preuve cette conversation entre un «marxiste de Kampala», une Algérienne et une Égyptienne qui porte le voUe. Cette dernière dira : «La question du voue est devenue une question économique au cœur même de la question reUgieuse.» Mais encore ?

Voyez-vous, ce n’est pas uniquement à cause de la

religion que nous portons le voile. Si une femme n’a pas les moyens de s’acheter toutes ces crèmes de beauté qui coûtent cher, les cosmétiques, les rouges à

lèvres, vous comprenez, c’estplusfacile ainsi.

N’importe quoi ! C’est Yolande Geadah, dans son exceUent/fewmes voilées, intégrismes démasqués (VLB, 1996), qui tient la seule position acceptable :

Malheureusement, il n’appartient pas à quelques- unes, aussi sincères soient-elles, de donner au voile un sens libérateur alors qu ‘il estprôné activement par un mouvement intégriste puissant, ouvertement en

faveur de la domination d’un sexe sur l’autre et delà limitation de la participation des femmes au seul domaine domestique.

« De Lahore à Montréal se compose le plus souvent d’une suite de pirouettes irrévérencieuses taquinant la rectitude poUtique », peut-on Ure en quatrième de couverture. C’est rire du monde. De Lahore à Montréal est un ouvrage réactionnaire, démagogique et méprisant. C’est faire œuvre de salubrité pubUque que de dénoncer un déUre à ce point racisteethaineux.

translated

Courrier des lecteurs

Dans le numéro 88, (hiver 1997) de Lettres québécoises Francine Bordeleau a attaque mon roman De Lahore à Montréal. Mais il y a quelques petits oublis et un paradoxe non négligeable. Elle affirme que le protagoniste du roman est néo-marxist et fanonist, tout en étant un reactionnaire favorable à la shariah. Fanon a pourtant défendu le role de femme en Algérie comme le protagoniste du roman appuie la lutte des femme au Pakistan.

Pour ce qui est racisme, le roman n’attaque pas seulement les très susceptibles Québécois. Il denounce aussi des Pakistanais comme sataniquement raciste.

Bordeleau protege son Québec et néglige le fait pourtant évident que le roman ridiculise plusieurs nationalismes; elle insiste sur les commentaires concernant le partitionisme (séparatisme) québécois. Mais elle omet les passages qui exposent le racisme:

“J’exhibai mon passeport canadien et ma carte de citoyenneté qui datait de 1973. Mais le responsable québécois réclama que je produise un formulaire IMM 1000 de l’immigration canadienne (il faut deux ou trois mois pour l’obtenir). Je suis arrivé au Canada en 1966. On me demandait de prouver que j’étais Canadien au bout de vingt-sept ans alors que je détiens un passeport canadien depuis plus de deux décennies.”

Où a-t-elle été éduquée? Au London School of Economics comme Jacques Parizeau? Imaginez qu’en tant que maire sortant d’une ville de France, il impute sa défaite à “l’argent et au vote ethnique.” On dirait de lui qu’il est lepenniste. Je me demande ce qu’en dirait Bordeleau.

Julian J. Samuel

Réponse:

Je vous remercie d’avoir commenté mon texte bien que nos positions soient irréconciliables, car je maintiens ce que j’ai écrit. Pour ce qui concerne les femmes, je vous ferai remarquer que le (néo) marxistes ne sont pas forcément les plus grands féminstes. Et si votre livre “ridiculise plusieurs nationalismes” en effet, il attaque avec un hargne particulière celui des Québécois – et le Québec en géneral, de toute facon. Je “protege [m] on Québec”, dites-vous ; je crois plutot avoir montré qu’il ya des limites à l’autodéstestation et à l autoflagellation. Non, le Québec n est pas un enfer raciste héritier du III Reich!

Francine Bordeleau

*

First Novels – Handicap, Hackles, Hong King, Horror

by Eva Tihanyi

http://www.booksincanada.com/article_view.asp?id=701

In contrast, Julian Samuel’s Passage to Lahore (Mercury, 240 pages, $15.95 paper) seems to have been designed to be deliberately provocative and deals much more with issues than with people. It rushes head-on into as many controversial arenas as it can: racism, colonialism, prejudice of all kinds-and that’s just for starters. No-one is spared a critique: gays, feminists, separatists, religious fundamentalists, intellectuals, non-intellectuals, the poor, and the wealthy. The subtitle is “A Novel”, but the book’s tone and format suggest a memoir disguised as fiction. The author uses his own name and alternates between first and third person points of view.

Samuel is sure to raise hackles, mainly because he has the nerve to voice opinions, some of which will undoubtedly be unpopular. For example, he recounts how as a Pakistani child growing up in England a bully “kicked the shit out of me.” When he tells the story to a “white straw-haired Canadian friend”, the friend tells him that “when he lived in France the same thing happened to him, even though he was white”-a situation about which Samuel observes: “However, when I write about or discuss my memories I can, if I want to, call it racism; he can’t. I can try to make a profit out of it, even get a grant; he can’t.”

As Samuel illustrates again and again: hypocrisy is evident everywhere and is not restricted to any one group. Unfortunately, his generally pedantic approach becomes overbearing; the book is more a treatise than a novel. At one point, he refers to himself as a “freelance intellectual”. By the end, one is left with the impression that he had set out to settle a lifetime of scores, and succeeded.

LE DOGME DE L’IMMIGRATION (45)

Récit de l’errance et de l’immigration

Qui aurait pensé qu’un jour le Ministère de la Culture du Québec et le Conseil des Arts du Canada subventionneraient un livre prônant la violence et la haine raciale contre les Québécois ? Car c’est bien là le scandale. Passé inaperçu.

lundi 28 décembre 2009 326 visites 4 messages

Oubliez la Gazette. Oubliez le National Geographic. Oubliez Diane Francis et Mordicai Richler. Oubliez les Nemni. Oubliez même Pit Bill Johnson. Parce qu’avec Julian Samuel, on atteint le fond de baril. Les bas-fonds du mépris. La haine totale.

Pakistanais d’origine, cinéaste raté de la gogauche Guili-McGilloise, Julian Samuel vivote de l’Aide sociale et des subventions gouvernementales (P.62 et P.197)) depuis une dizaine d’années dans un Montréal qu’il déteste. Dans un livre publié en 1996, qui est passé inaperçu mais qui pourtant avait tout pour faire scandale, Samuel déverse son fiel sur TOUT ce qui est québécois, allant jusqu’à prôner la violence et la haine raciale.

Sur 253 pages, qui vont de Lahore à Montréal (d’où le titre), en passant par Alger et Hongkong, l’auteur ne trouve pas un seul mot positif à dire de la Métropole, du Québec et des Québécois. Rien, mais absolument rien de québécois ne trouve grâce aux yeux du pseudo-cinéphile. Pas même notre Céline nationale (“une chanson merdique beuglée par Céline Dion”, P.124).

Les tours du Complexe Desjardins sont “de grands bâtiments hideux en béton”, un “monument au mauvais goût sans pareil dans le monde occidental” (P.111).

Nos dramaturges sont des “trous-de-custes qui ont fait de votre langue vernaculaire une langue de palais” (P.102). De toute façon, notre “français est une abomination” (P.151). Les oeuvres de Tremblay, pourtant traduites dans une trentaine de langues, n’ont aucune envergure internationale. “Ce ne sont que des tranches de vie sans véritable dimension culturelle, c’est ennuyeux, vraiment. (P.152-153)”

L’ONF, qui croule sous les Oscars, est réduit à “une boîte de production sans intérêt”… qui produit… “des documentaires visuellement tristounets… (sur) des thèmes ennuyeux” (P.62). Nos cinéastes font des films redondants sur la vie sexuelle de quelques professeurs bébêtes, de leurs femmes et de quelques trous de cul antigays (P.149) “. Radio-Canada est “infiniment assommante” (P.65).

Nos étudiants “ont sans doute, le plus bas niveau de sensibilisation aux questions internationales” (P.66). Imaginez : “Les Algériens peuvent situer Maputo sur une carte. (Mais) Les jeunes Québécois ne savent pas ou ne veulent pas savoir où se trouve Luanda ou à quel moment Maputo a été une ville coloniale portugaise” (P.66).

Même la bouffe québécoise, réduite à “quelques fast-foods de poulet prêts-à-emporter” (P.147), fait lever le coeur au gastronome pakistanais. “Les Français sont repartis chez eux et on a fait frire le poulet pour le servir dans une sauce à la recette secrète.” (P.147) (A-t-il déniché un colonel Saulnier que nous ignorions ?)

Pour Samuel, le Québec est “un Etat-province qui se fonde sur bien peu de choses sauf, peut-être, une industrie de la mort qui vend d’énormes quantités d’armes à des pays en guerre…sauf peut-être un parler français extrêmement régional” (P.147).

Bien que vivant à Montréal depuis 11 ans, le camarade a appris plus de nouveaux mots français durant un court séjour en Algérie que pendant toutes ces années passées ici (P.58), ce qui en dit long sur son intégration. D’ailleurs, à peu près tous les Montréalais qu’il connaît ne sont pas Québécois.

Féministe, mais affreusement macho. Tiers-mondiste, mais faisant le trafic des devises en Algérie (P.67). Prolétarien, mais méprisant pour les serveuses québécoises dans les restaurants, sympathique à toutes les révolutions, de la Commune de Paris aux Palestiniens, en passant par l’Algérie et l’Afrique du Sud, Samuel demeure enragé rare contre les Québécois qui le font vivre depuis 11 ans avec leurs taxes et impôts.

“Les Québécois (sont) étroits d’esprit…(P.101). Le nationalisme de bazar, ça ne vaut pas de la merde” (P.101). “Les leaders du PQ ont l’air de protonazis” (P.50). La politique de régionalisation de l’immigration est contrôlée par des nationalistes machiavéliques (P.103). Des “planificateurs de la nation québécoise hostiles aux immigrants ont tâché d’imaginer de nouvelles façons de déplacer les nouveaux arrivants vers des villages en périphérie de Montréal, vers la fin du vingtième siècle, de façon à ne pas indisposer la population “authentique” de cette ville.” (P.103)

Le récit d’Oka où “les événements dans la réserve indienne ont démontré cette tendance protofaciste des Québécois” (P.144) est un pure chef-d’oeuvre de désinformation stalinienne. “On coupa les vives aux Warriors. Pendant leur détention, plusieurs de ces “communards” ont été battus comme des bêtes par les agents de la Sûreté du Québec. Peut-être bien que le gouvernement du Québec exilera les Warriors vers la Nouvelle-Calédonie tout comme l’a fait le régime français avec les communards, après 1871. C’est ça le Québec à mes yeux” (P.145). Une “Bande de crétins” (P.147).

“Voici donc les frontières québécoises : l’armée à Oka, la diffusion de films hostiles aux immigrants sur les ondes de la télévision nationale aux heures de grande écoute, et les refus que je dois essuyer” (dans sa démarche pour obtenir une subvention pour faire un film). “Seul un soulèvement racial violent pouvait leur ouvrir l’esprit” (P.103).

Qui aurait pensé qu’un jour le Ministère de la Culture du Québec et le Conseil des Arts du Canada subventionneraient un livre prônant la violence et la haine raciale contre les Québécois ? Car c’est bien là le scandale. Passé inaperçu.

*

“De Lahore à Montréal”, Julian Samuel, Les Éditions Balzac, 253 pages. 1996

http://www.juliansamuel.net/02.html

Récit de l’errance et de l’immigration, Julian Samuel nous entraîne dans ses souvenirs d’enfance et d’adolescence, de Lahore jusq’en Angleterre, puis Toronto, pour aboutir à Montréal, où l’auteur vit désormais. Cette expérience de vie, Julian Samuel ne craint pas de nous la narrer avec l’emportement, les idées et les impairs qui lui sont propres. Julian Samuel irritera certains âmes sensibles, surtout parce qu’il a toupet d’émettre des opinions dont certaines seront très mal reçues, mais ses critiques et le tir groupé de Julian Samuel sont atténués par son sens de l’humour, quelque peu cabotin certes, mais qui se révèle le plus souvent perspicace et sonne juste.

http://www.juliansamuel.net/02.html

Suggérer cet article par courriel

Vos commentaires:

Récit de l’errance et de l’immigration

28 décembre 2009, par André Gignac

Monsieur Noël,

Un “crackpot” comme ça, tu lui fais prendre le premier avion pour Lahore en billet simple ! J’envoie votre texte à la Ministre de la Culture à Québec. Maudit qu’on est donc du bon monde ici au Québec et patient en plus comme c’est possible ! Beaucoup de coups de pieds au c.. se perdent par les temps qui courent. Bonne Année 2010 !

André Gignac le 28-12-09

Récit de l’errance et de l’immigration

28 décembre 2009, par Marie Mance Vallée

En effet, un billet aller, direct pour Lahore. Et la minisse devrait l’accompagner.

Comme nous sommes généreux, nous leur paierons leur billet.

Et la minisse, une autre, qui est en-dessous de tout.

Quelle misère nationale !

Récit de l’errance et de l’immigration

28 décembre 2009, par Gébé Tremblay

“To Jews as Jews we bear no malice ; to Jews as Zionists, intoxicated with their militarism and reeking with technological arrogance, we refuse to be hospitable.” (Prime Minister Z. A. Bhutto, 1974)

« Le Juif reste Juif même quand il change de religion. Un Chrétien qui adopterait la religion juive ne deviendrait pas pour cela un Juif. Parce que la qualité de Juif ne tient pas à la religion, mais à la race et qu’un Juif libre penseur ou athée, demeure aussi Juif que n’importe quel rabbin.» (Jewish World 1922)

Dans tous les livres, les articles, les films, de Julian Samuel il utilise au moins une fois l’holocauste pour faire un point et quelques fois les “Nazis” pour faire comparaison aux impérialistes. Il peut se dire athée, jouer à l’anti-sioniste ou au révolutionnaire progressiste autant qu’il veut, il pratique fidèlement son culte et en retire les bénéfices.

Les opinions de Julian Samuel ne me choquent pas ni me blessent, je lui reconnaît la liberté d’expression comme à tous les hommes.

Ce qui est scandaleux, parcontre, c’est que si moi ou un des miens souhaite en faire autant envers son groupe à lui, on me refusera toutes subventions et même publication et dans l’éventualité qu’un éditeur courageux publie tout de même, les librairies qui l’afficheraient se verraient attaquées et vandalisées comme celà se fait en Europe.

Il faut donc mettre son culte à l’épreuve, car nos institutions en sont les plus croyants fidèles.

Récit de l’errance et de l’immigration

28 décembre 2009, par Grand-papa

Vraiment il exagère cet auteur, s’en est presque drôle…Je suis d’accord avec les extraits suivants du livre que vous citez :

« Radio-Canada est “infiniment assommante” (P.65). »

« Pas même notre Céline nationale (“une chanson merdique beuglée par Céline Dion”, P.124). »

« Des “planificateurs de la nation québécoise hostiles aux immigrants ont tâché d’imaginer de nouvelles façons de déplacer les nouveaux arrivants vers des villages en périphérie de Montréal, vers la fin du vingtième siècle, de façon à ne pas indisposer la population “authentique” de cette ville.” (P.103) »

« Le nationalisme de bazar, ça ne vaut pas de la merde” (P.101) »

Salutations