“Atheism” confronts religion and its discontents by introducing the views of a physicist who refutes the Big Bang, and with it the possibility of a creation; a novelist who uses post-Newtonian concepts as a story-telling device; two experts on Islam; a Christian thinker from within the church; an atheist, originally from an Islamic country; and a philosopher who topples the world of miracles by subjecting them to the rational waters of logic upon which, it emerges, one can’t walk, despite surface tension.

Julian Samuel

ATHEISM

72 minutes, 2006, a talking-heads documentary l

Official competition: Atheism, Jogja-Netpac Asian Film Festival

Official selection: La 35e édition du Festival du nouveau cinéma: 2006

http://www.nouveaucinema.ca/EN/

http://www.nouveaucinema.ca/2006/fiche_film.php?id=06-9251

*

QUOTATIONS FROM REVIEWS:

This film by Julian Samuel has to be the most intellectually dishonest documentary ever produced. Samuel has produced a subjective and biased reflection on religion and the question of whether a Supreme Being organized the Universe…

…an example of this bias is when Professor Samuel has his interviewees discuss the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and the Bush administration’s foreign policy in a clearly anti-Israeli and anti-American way. What this has to do with atheism, spirituality or even a theological reflection on the meaning of life is anyone’s guess.

Frederic Eger: Atheism by Julian Samuel

http://www.theepochtimes.com/news/6-11-7/47843.html

29 November 2006

Like Richard Dawkins’ much-discussed recent book The God Delusion, Atheism makes not the slightest attempt to win over anyone who might feel that there’s any validity to spiritual beliefs.

Montreal Mirror, 30 November 2006: God be damned

MALCOLM FRASER

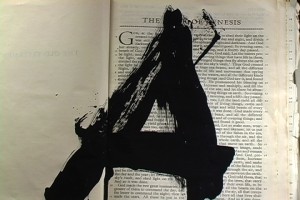

Samuel is either unfamiliar with film language or unwilling to engage with it, and it’s a shame, because this non-professionalism compromises his film. Some of his on-camera shock techniques – including the opening credits, which depict a hand tarring a Bible with the film’s title (and Samuel’s own name, one letter at a time) – are laughable and tedious.

HOUR: 30 November 2006; God day afternoon, The anarchy of atheism

Melora Koepke

* 1/2 – Atheism, documentaire de Julian Samuel. Quelle place occupe Dieu dans le monde, la philosophie, la politique? L’athéisme est-il une religion?

Un documentaire prétentieux et vain. On est loin de la révolution copernicienne.

Ce qui rend ce film méprisable n’est pas tant que l’on n’y apprend rien de neuf, mais plutôt la façon dont ce rien de neuf est emballé: c’est pédagogiquement nul et cinématographiquement pédant. Tant mieux si le réalisateur s’est amusé, car nous, on s’est plutôt mortellement emmerdés.

La Presse, 2 December 2006; Atheism : quand le spirituel déprime

Anabelle Nicoud, Collaboration spéciale

Julian Samuel explique pourtant que son film entend poser un regard sur la manière dont un athée comme lui est devenu une personne religieuse. Atheism un prouve en fait rien de tel. Il soulève des questions, met bout à bout des croyances et des incroyances, laissant au spectateur ses propres convication quant au reste.

Le Devoir, 1 December 2006,

Odile Tremblay: “Croire ou ne pas croire”

*

Interviewees:

Tariq Ali, author,

The Clash of Fundamentalisms

Fadi Hammoud,

Journalist and

Middle East specialist

Alison MacLeod, author,

The Wave Theory of Angels

Christine Overall,

Professor of Philosophy, Queen’s University

Jean-Claude Pecker, astrophysicist

Collège de France and Académie des Sciences, Paris (retired)

Noomane Raboudi

Specialist on Islam

John Shelby Spong

former Episcopal

Bishop of Newark, NJ.

*

REVIEWS IN ENGLISH AND FRENCH

Sylvat Aziz

This visual essay, comprising scholarly and accessible interviews, should prove to be universally provocative in the most positive sense. Comparisons between science, revealed and other religions, artistic values and histories place a premium on reason. Although the title/topic is exceptionally large and in its nature sociopolitically charged, in this case theism and atheism are discussed intelligently and expertly using language that avoids jargon. A most refreshing circumstance. One can find a sensitive clarity throughout, a sense of humour in the background, poignant and at times with a bite, that extenuates the fragility of complex systems of human thought discussed herein.

Although the video strays from strict documentary form, dogmas, beliefs, habits and so on are discussed without promulgating a particular dogma, belief, habit.

The more abstract visual references insinuated in the video; the use of stained glass windows, overlaid gestural calligraphy, references to religious icons and ritual practices, allusions to biological beginnings and other visual elements, are sometimes more successful than others but on the whole, these serve as a practical as well as symbolic matrix for the interviews, adding a relevant visual textural interest. The framing is direct and strong avoiding clutter, making content confident.

In the main the value of this essay lies in its humane, non-proselyitizing position and the thoughtful responses to questions concerning many facets of this very complex, essentially human set of ideas.

Official selection: La 35e édition du Festival du nouveau cinéma: 2006:

http://www.nouveaucinema.ca/2006/fiche_film.php?id=06-9251

“Quelques personnes se doivent de faire des documentaires intellectuellement fouillés et denses, sinon nous ne ferons que des trucs comme The Corporation, Bowling for Columbine et tous ces trucs qui sont visuellement divertissants, humoristiques, légers mais qui n’ont que très peu de profondeur analytique.” Ce commentaire controversé, Julian Samuel le formulait en 2004 après la sortie de son documentaire Save and Burn, sur ce qu’il appelait la mort des bibliothèques. Fidèle à sa démarche exigeante et intellectuelle, il nous revient avec une réflexion sur l’athéisme en cette période de grands troubles idéologiques et religieux. Est-ce une nécessité ou une absurdité pour l’homme de prétendre à l’athéisme? Universitaires et penseurs s’offrent à la caméra de Samuel pour bousculer deux ou trois idées reçues.

*

Jeff Sims, Philosophy and Religious Studies

Julian Samuel’s most recent documentary, Atheism, poses a vigorous and provocative challenge to what are primarily (but not exclusively), Semitic brands of theism both cherished and challenged in the western, intellectual world. With 71 minutes of film on hand, Samuel endeavors to discover what might reasonably be said of this elusive and, perhaps, too transcendent theme. Theism, Samuel suggests, sardonically permeates our human, all too human history, lending itself precariously to the wayward advances of political authority, underwriting a host of societies around the globe.

Using a broad range of interview subjects – portraying graphic illustrations of our most candid thoughts – and each with their own discriminating sense of interpretation, Samuel speaks with physicists, philosophers, bishops, political scientists, and Middle Eastern scholars, all in an effort to delineate a sensible understanding of a most insensible topic. Samuel’s Atheism should come as highly recommended viewing for both the irreligious, and still, religious thinker of the 21st century.

*

Robert Wiechec

Le film “Atheism by Julian Samuel” interroge sur la question d’absence de Dieu dans la vie du monde. Le documentaire nous plonge rapidement dans les réflexions et positions émanant des divers interrogés. Cette démarche produit un remarquable tableau des éventualités. Les questions d’encrage religieux prennent place. Les croisades, les guerres, l’Inquisition et le mystère. Par opposition, elles sont suivies par d’intéressantes interrogations d’ordre scientifiques et philosophiques du réel.

Pour l’auteur une œuvre d’art doit questionner. C’est à cela que nous assistons. À travers des interviews, Julian Samuel sonde subtilement les sensibilités de ses interlocuteurs pour ensuite les confronter avec les siennes. Cette démarche très instructive sur les positions athées possibles a aussi pour but sa propre auto-reconduction. L’auteur tente une confrontation et essaye de réaffirmer, une fois encore, le choix qu’il avait fait à l’âge de ses 16 ans. Les loyaux de Julian Samuel, à voir impérativement. Ce film va vous saisir.

*

Atheism, 71 minutes, 2006. A documentary by Julian Samuel.

published: 1 October 2006:

http://www.montrealserai.com/2006_Volume_19/19_3/Article_7.htm

Review by

Maya Khankhoje

[Maya Khankhoje, who has no religious affiliation, believes that the study of religion is important because the latter both shapes, as well as reflects, human behaviour.]

“This film”, announces Julian Samuel’s deep voice, “is a look at how an atheist like me becomes a religious person”. To prove his point, he interviews people placed on either side of the religious/atheist divide: Tariq Ali, author of “The Clash of Fundamentalisms”; Fadi Hammoud; Journalist specializing in Middle Eastern Affairs; novelist Alison McLeod, author of “The Wave Theory of Angels”; Christine Overall, Professor of Philosophy at Queen’s University; Jean-Claude Pecker, retired astrophysicist and member of Académie des Sciences, Paris; Noomane Raboudi, specialist on Islam and John Shelby Spong, former Episcopal Bishop of Newark.

From the outset, Samuel warns his viewers that some scenes might be shocking: the juxtaposition of condoms and photographs of Pope Pius XII (whose leadership of the church during the holocaust raised many eyebrows); raunchy clay figurines smashed on a Bible; a primeval Eve sliding naked on a tree branch; the word ATHEISM tarred on a Bible; fish and chapattis (instead of loaves of bread) miraculously multiplied not by a benevolent Christ, but by clever computer graphics; a triumphant Mussolini riding in full regalia on a wall behind the altar of a Montreal church and many more. If the images do not succeed in shocking modern viewers inured to the anything-goes tenor of the media, they will certainly goad them into questioning their religion, be it Christianity, Islam or an all-knowing Cartesian rationality. Other major religious systems are barely touched upon, a limitation not mentioned by the author, nor is the spiritual dimension brought into the equation.

The structure of the film is the traditional piecing-together of snippets of interviews taken at different times and locations, which creates the illusion of an ongoing discussion amongst various thinkers, threaded together by the interviewer’s voice. This is done quite successfully. For the most part the film-maker keeps off our visual and audio reach, although occasionally extreme close-ups of his face pop into the narrative, interrupting its flow. At other times, his camera work is a bit wobbly, but this is a very minor fault in an otherwise well constructed film.

The strongest point of the film is the variety of very articulate voices who speak, not on the subject of atheism as the title would suggest, but rather on the subject of Christianity and Islam and their effects on politics. For Tariq Ali, the United States is a society suffused with religion, where 90% believe in the deity, 70% believe in angels and 60% believe in Satan. We can imagine Ali smiling as he quotes Goethe who said that if you believe in the devil, you are already in his clutches! He also reminds us that all fundamentalisms share the same features. For him, there isn’t much of a difference between the Bali bomber who killed many Australians and the American anti-abortionist who killed doctors on behalf of God. Noomane Raboudi explains how many current regimes like Saudi Arabia and Israel, would have no legitimacy were it not for the belief that God had privileged their territories. He also points out that American Imperialism has broken the backbone of the movement towards Arab unity started by Nasser. Christina Overall strongly believes that there is no evidence that atheists or agnostics are any less moral than religious believers and warns us that whilst religion is more efficient at inculcating moral values, these values are not necessarily desirable, such as the inferiority of women and of entire groups of people. She also laments that the church turned away from Ibn Sina (Avicenna) the great medieval physician of the Islamic world, because it felt threatened by his knowledge. Fadi Hammoud points out that the Islamic world is not monolithic and that there have always been atheists in its milieu, going as far back as the Abbassid caliphate from 749 to 1258. Alison McLeod makes a plea for wonder and curiosity which she deems “a moral function”. Jean-Claude Pecker sees time as an infinite function, thereby endorsing Aristotle’s non-creationist viewpoint. He also points to the flaws in the Big Bang theory which some Christians have renamed Intelligent Creation and incorporated it into their creationist theory. John Shelby Spong affirms that “any system of economics or politics that denigrates any human being cannot be of god”.

This film, like any piece of art worth its salt, raises more questions than it answers. It does so within the limited framework of two world religions engaged in a modern-style crusade, and a third religion playing a surrogate role in an expansionist game which has nothing to do with the expansion of the universe and all to do with creating black holes in other people’s territories. However, there is still a lot of work for this independent film-maker to tackle, both in terms of technique as well as focus and content. For starters, he could explore how major pre-Biblical religions have shaped the culture of millions of people throughout the world. And he could end with a more complete analysis of how religion and politics form a toxic brew which is poisoning the shared civilization that humanity has constructed over several millennia.

If Julian Samuel believes that a journey through his film will lead from atheism to theism he is either sadly mistaken or his tongue has stuck to his cheek. What can happen, however, is that believers in the creationist theory posited by the Bible as well as believers in the Big Bang theory posited by some astrophysicists will both be shaken to the core.

Samuel’s film is an excellent example of how art can subvert the powers-that-be, in this case, the religious establishment.

*

29 November 2006

by

Frederic Eger

http://www.theepochtimes.com/news/6-11-7/47843.html

This film by Julian Samuel has to be the most intellectually dishonest documentary ever produced. Samuel has produced a subjective and biased reflection on religion and the question of whether a Supreme Being organized the Universe. Shot with nonprofessional camera equipment, the filmmaker interviewed a questionable choice of “experts”—the author of a book on angels, a Lutheran minister, and journalists reporting on the Middle East and religious fundamentalists.

From beginning to end, the documentary focuses on the existence of a Supreme Being and only two religions, Islamism and Catholicism. The filmmaker does not interview a Buddhist monk or master, the Dalai Lama, a Hindu swami, or rabbi. He doesn’t even bother to talk with an ordinary devotee or disciple of any oriental religion, nor does he discuss the issue with a representative panel of all major religions.

By doing so, his objective seems obvious—nothing will challenge his initial thesis: “We atheists are right. There is no such thing as a God. Religious people are totalitarian and ideologically-oriented. Religions started the crusades and jihads and repress anyone who doesn’t believe in God.”

Even if it is correct to say that religions start wars and inflict human suffering, the film reduces this statement to its lowest level and never mentions the word, much less the concept, of spirituality. It excludes the fact that you can believe in a Supreme Being or Force without belonging to any religion. And that’s probably the unforgivable weakness of this documentary. It ends up as the biased work of an atheist eager to poke fun at believers.

An example of this bias is when Professor Samuel has his interviewees discuss the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and the Bush administration’s foreign policy in a clearly anti-Israeli and anti-American way. What this has to do with atheism, spirituality or even a theological reflection on the meaning of life is anyone’s guess. The film devolves into a narrow pseudo-examination on possibly the most intriguing issue of our time.

Pakistani-born Concordia Professor Julian Samuel should probably enroll in some journalism classes to learn the basics of the craft. He would learn about journalistic honesty or, as one of my professors, Stephane Manier, used to say: “Verifying information and presenting contradictory views are what differentiate journalism from rumor, if not defamation.”

Atheism – Written, Directed & Produced by Julian Samuel, Runtime: 72 min

*

Montreal Mirror, 30 November 2006:

God be damned

Julian Samuel’s Atheism is a densely theoretical attack on religion

by

MALCOLM FRASER

Local filmmaker Julian Samuel flies the flag for religious nonbelievers in his challenging new documentary, simply titled Atheism. Samuel caused a little stir in the documentary world a couple of years ago when he slagged off Bowling for Columbine, The Corporation and their pop-cultural ilk as intellectually lightweight. As befits this perspective, Atheism is an extremely dense work devoid of any fluff or comic relief.

Samuel lines up an assortment of thinkers to share their opinions on the topic: activist and The Clash of Fundamentalisms author Tariq Ali, former Episcopal bishop John Shelby Spong, novelist Alison MacLeod, Queen’s philosophy prof Christine Overall and others. In what can only be considered either a bold throwing down of the gauntlet or a spectacularly ill-advised gesture of audience alienation, Samuel begins the film with MacLeod reading a lengthy excerpt from a book about physics. The subject matter is impenetrable and the text full of jargon, besides which MacLeod is reading from her lap, only occasionally glancing up at the camera.

From this peculiar opening salvo, Samuel dives into a rigorously analytical assault on religion, mixing interview clips with occasional personal reflections and assorted abstract or provocative imagery. The film’s style veers from the obscurism of late Godard (at one point, a quotation in black text is absurdly superimposed on a mostly black background, making it impossible to read) to the slapdash aesthetic of Ed Wood (during one of Ali’s interview segments, he tilts his head, clearly revealing a doorknob gleaming in the black background behind him). Since Samuel is an experienced filmmaker (this is his fifth film since 1994), we have to assume these odd choices are deliberate, but they’re still inexplicable.

Like Richard Dawkins’ much-discussed recent book The God Delusion, Atheism makes not the slightest attempt to win over anyone who might feel that there’s any validity to spiritual beliefs. Rather, it’s an insiders’ discussion by, about and for atheist intellectuals. As such, it contains a lot of interesting information and a few thought-provoking insights. But the unrelenting density and the muddled style might leave you feeling like the morning after a drunken philosophical debate in university: moderately enlightened but undeniably confused, and possibly with a bit of a headache.

Atheism opens this Friday, Dec. 1, 2006 at Ex-Centris

*

HOUR: 30 November 2006

God day afternoon

Melora Koepke

The anarchy of atheism

What if God was one of us, asks Julian Samuel in his new doc, Atheism

Montreal documentary-maker Julian Samuel has wisely discerned that the time is ripe for an investigation into the question of the existence of God and the place of His believers in the world.

Atheism is Samuel’s investigation into the viability of religious belief from both a cultural and a personal perspective. Its collection of talking heads includes the authors of The Clash of Fundamentalisms and The Wave Theory of Angels, a retired astrophysicist from the Collège de France and the former Episcopal bishop of Newark, among others. The experts are cut with various dramatic visual effects, and the filmmaker offers a loose non-fiction narrative in which, he promises, his own atheism will be interrogated.

“This film is a look at how an atheist like me becomes a religious person,” intones Samuel near the beginning of Atheism. If this storyline sounds disingenuous, that’s because it may well be. But Samuel, admirably, has been a vociferous critic of the cut-and-slash approach of documentarists like Michael Moore, who incite the public to their facile conclusions with cheap, sexy tactics and lazy analysis. Atheism is clearly not made for the same fans of reality video who enjoy The Simple Life – in the first sequence, Samuel allows an interviewee to read aloud from her book for several minutes, in one long shot.

Though there is nothing wrong with letting a talking head talk for a while, there’s really no excuse for framing and lighting said talking head so badly that the thing looks like it was shot as a high-school social studies project from the ’80s. In this day and age, there really is no reason for a movie to be this messy.

Like it or not, film is a visual medium that should take into account the people who are actually watching the film. Samuel is either unfamiliar with film language or unwilling to engage with it, and it’s a shame, because this non-professionalism compromises his film. Some of his on-camera shock techniques – including the opening credits, which depict a hand tarring a Bible with the film’s title (and Samuel’s own name, one letter at a time) – are laughable and tedious. Others (clay statues smashed, the stained-glass window of a cathedral shot with shaky-hand cam, condoms thrust next to an image of the Pope) are downright infantile. Sadly, these unfortunate details discredit the interesting points his interviewees make.

And when, near the end, it becomes apparent that the filmmaker’s non-faith remains unshaken after all, we are barely surprised.

*

Voir: 30 November 2006

http://www.voir.ca/cinema/cinema.aspx?iIDArticle=44943

Atheism

N. Wysocka

Après Save and Burn, qui traitait de ce qu’il avait surnommé la mort des bibliothèques, le réalisateur montréalais Julian Samuel, reconnu pour bousculer les convenances, revient à la charge avec un documentaire portant cette fois sur la question de l’athéisme. Au travers des témoignages livrés par des universitaires et des penseurs, Samuel propose d’illustrer comment un athée devient croyant. Bien que certains d’entre eux parviennent à soulever quelques points de vue intéressants, le discours ampoulé qui parsème cet Atheism risque de ne pas plaire à tout le monde. On parvient néanmoins à oublier momentanément la réalisation artisanale et le léger manque de rythme lorsqu’un physicien déclare que le Big Bang n’a jamais eu lieu. Ah bon? À prendre… ou à laisser.

*

JOHN GRIFFIN

The Gazette

Friday, December 1, 2006

Julian Samuel’s new documentary begins with a hand and a brush, angrily stroking black paint on the printed pages of a book. Slowly the letters form as the pages are turned, and the book becomes familiar, as familiar as any book in the world. It is the Bible, and the letters come together to form the title of the film – Atheism. It is a typically inflammatory start for this city’s most opinionated firebrand, which makes the work to come all the more unusual. Over the next 70 minutes, Samuel painstakingly interviews several world authorities on science and organized religion to form a reasonably balanced account of the ills wrought upon civilization by belief in a single, omnipotent god.

They include writers like Tariq Ali, whose book, The Clash of Fundamentalisms, might be written for the state of the world as the sun comes up today.

The French scientist Jean-Claude Pecker reacts to religion with the skepticism of his chosen profession, while journalist Fadi Hammoud talks about the terrorist state in analogies involving lids on pressure cookers, and their removal. Saddam Hussein’s name will be mentioned.

Christine Overall, a professor of philosophy at Queen’s University, describes the intellectual process that lead her away from the church to atheism – she would come back happily if persuaded God existed; and John Shelby Spong, former Episcopal bishop of Newark, N.J., speaks passionately and with wisdom about God as a mystery beyond human comprehension.

Intercut like visual bottle rockets between these weighty talking heads are Samuel’s own impressions. A Bible page is entirely blacked out. Black paint is shaped into delicate calligraphy, vortexes of abstract expressionism, and lines on a road.

Church, temple and mosque icons are assessed monetary value; a gorilla is repeatedly shown as a symbol of the recent Christian right’s embrace of Intelligent Design over Darwinism; the director himself is seen standing in the shadow of a church, and, in archival footage, announcing his own atheism over a home radio at the age of 16.

There are the outbursts expected of Samuel, our most professional hothead and reliable thorn in the side of a real or imagined establishment.

They throw a wrench into what is otherwise a reasoned report on religion, one of the day’s most pressing issues. They have not affected the ultra-low budget film’s ability to screen at the recent Festival du nouveau cinema, or enjoy a commercial run at Ex-Centris from today to Tuesday. It would be a shame if they hurt Atheism’s chances at a broader audience. The film deserves to be seen, absorbed, and discussed, loudly, with arms waving.

Atheism

RATING 3

Documentary

Playing at: Ex-Centris cinema.

Parents’ guide: shocking images.

© The Gazette (Montreal) 2006

*

JOHN GRIFFIN, The Gazette

Friday, December 2, 2006

This is #736 in a series about local artists who won’t take no for an answer. Julian Samuel is a documentary filmmaker, author and painter whose new film Atheism is playing at Ex-Centris through Tuesday. Writer-director Benjamin P. Paquette’s first fiction feature A Year in the Death of Jack Richards is playing Cinéma du Parc until Thursday. By any conventional form of logic, neither should ever have seen the light of day. Atheism is Samuel’s third doc, after 2002’s The Library in Crisis and Save and Burn, in 2004. For some reason, his story about the role of organized religion in the ruinization of the world as we know it was rejected by various funding agencies, seven times running. Undeterred, he carried on. “The funding enterprises were useless,” says Samuel, who has been known to speak his mind. “So I made it myself, with a digital camera, for less than $8,000.” Samuel was blessed that many of the people he wanted to speak to either lived within easy travel range, or happened to pass through town. All offer reasoned arguments, augmented by the director’s own, more volatile, artistic gestures. The first, and most controversial, is an opening sequence where he writes the film’s title in black paint on the pages of the Bible. “It’s not been a problem in Canada, and especially not in Quebec, where the claws of God haven’t ripped out the intestines of society. But American distributors say it’s too confrontational. I’ll have a hard time getting it shown there.”

*

Atheism : quand le spirituel déprime

Anabelle Nicoud

La Presse, 2 December 2006

Collaboration spéciale

* 1/2 – Atheism, documentaire de Julian Samuel.

Quelle place occupe Dieu dans le monde, la philosophie, la politique? L’athéisme est-il une religion?

Un documentaire prétentieux et vain. On est loin de la révolution copernicienne.

Big Bang, monothéisme, agnosticisme, créationnisme, darwinisme, éloge de la raison, croisades et impérialisme, religion, arts et sciences. Après les grandes bibliothèques (Save and Burn), le réalisateur montréalais Julian Samuel aborde pêle-mêle ces sujets dans son dernier documentaire, Atheism. L’auteur du Clash des fondamentalismes Tariq Ali, le journaliste spécialiste du Moyen-Orient Fadi Hammoud, l’astrophysicien Jean-Claude Pecker, l’évêque de Newark John Shelby Spong, répondent, entre autres, aux questions (méta)-physiques du réalisateur. Indigeste? Oui, sur le fond, d’une superficialité époustouflante, comme sur la forme, d’une prétention incroyable. Tel un adolescent dissertant la spiritualité au troquet du coin, Julian Samuel amène ses interviewés à ouvrir des portes pourtant ouvertes avant lui. Rien de neuf dans les exposés oraux de M. Pecker sur le Big Bang comme version scientifique du fiat lux de la Bible ou les développements de Noomane Raboudi sur les «croisades» modernes de l’ami W en Irak comme résurgence des croisades chrétiennes du Moyen-Âge.

Ne comptons pas sur les effets visuels pour sauver le film. Pour ne pas sombrer pendant Atheism, il faut passer outre les essais prétendument artistiques et supposément choquants du réalisateur. Et pourtant… faire d’une séance de «Bible painting» un générique est pompeux plus que subversif. Quant au visage du pape Pie XII auréolé de capotes, l’idée pourrait être intéressante si elle était sous-tendue ou justifiée par le propos, ce qui est loin d’être le cas. Que le réalisateur joue avec la fonction zoom d’une caméra n’a rien de très trippant pour le spectateur. Pas plus que les effets de type «flou sur les gros plan, mise au point à l’arrière», procédé qui évoque plus la maladresse des films de famille qu’une démarche cinématographique, documentaire ou fictionnelle. On ne sait trop si le réalisateur oublie volontairement de mentionner qui sont ses intervenants quand ils apparaissent pour la première fois dans le film ou si cela procède là encore d’une démarche (mais dans quel but, si ce n’est de semer son spectateur…). Ce qui rend ce film méprisable n’est pas tant que l’on n’y apprend rien de neuf, mais plutôt la façon dont ce rien de neuf est emballé: c’est pédagogiquement nul et cinématographiquement pédant. Tant mieux si le réalisateur s’est amusé, car nous, on s’est plutôt mortellement emmerdés.

*

Le Devoir, 1 December 2006,

Odile Tremblay: “Croire ou ne pas croire”

Réalization et scénario: Julian Samuel. A Ex-Centris.

L’athéisme est un sujet en or, insuffisamment exploré au documentaire ces temps-ci alors qu’il y aurait tant à en dire. Aux Etats-Unis, s’avouer athée et se réveler non pratiquant ferme désormais les portes des fonctions politiques. Les théories évolutioniniste de Darwin se heurtent au créationnisme, si populaire chez nos voisins du Sud. L’athéisme est en position de recul en Amérique du Nord, sauf au Québec.

Le documentariste montréalais Julian Samuel s’est attaqué à la question, interrogeant croyants, philosophes et théologiens de toutes les doctrines, athée et agnostiques. Il en résulte une bonne syntése qui renovie bien entendu dos à dos adeptes de la foi et mécréants convaincus.

Sur le plan technique, la caméra de Samuel manque de tenue et vire souvent dans le flou. Ce film montre surtout des têtes parlantes, mais quand le cinéaste y greffe des images plus symboliques (dunes de sable, taches d’encre, etc), le resultat n’apparaît guère adroit. Le fait que des condoms se superposent à une photo de Pie XII ne choquera plus grand monde aujourd’hui.

“Athéisme” vaut surtout par ses questionnements. L’astrophysicien Jean-Claude Pecker explique à quel point la théorie du big bang fut récupérée à des fins créationistes. Le journaliste Fadi Hammoud rappelle que l’athéisme a également émergé des communautés islamistes. L’évêque de Newark John Shelby Spong estime qu’il faudrait cesser d’opposer science et foi car l’une complète l’autre. La philosophe Christine Overall démontre que les valeurs morales n’émanent pas davantage des sociétés religieuses que des régime non croyants.

Bref, de telles discussions par entrevues interposées se révèlent toujours passionnantes, même lorsqu’elles apparaissent forcément partielles. Encore que la dimension spirituelle des religions semble un peu évacuée ici, au profit des méfaits de l’aspect “opium de peuple”: guerres, inquisitions, etc.

Julian Samuel explique pourtant que son film entend poser un regard sur la manière dont un athée comme lui est devenu une personne religieuse. Atheism un prouve en fait rien de tel. Il soulève des questions, met bout à bout des croyances et des incroyances, laissant au spectateur ses propres convication quant au reste.

*

The McGill Daily, 12 February 2007

Local filmmaker puts a nail in God’s coffin

Talking heads deny the divine in an unabashedly propagandistic documentary

By Josh Ginsberg, Culture Writer

Clergy, pull up the drawbridge: a Montreal filmmaker has launched a frontal assault on religion.

Atheism, Julian Samuel’s newest documentary, pits God against the academy by lining up a cadre of intellectuals to deny the deity. Lacking a coherent narrative, the film builds a free-form argument by knitting together snippets from a battery of interviews. This leaves viewers with plenty to digest, but the audience’s degree of tolerance for talking heads will ultimately determine whether the experience is fascinating or flat.

Despite its cerebral tone, Samuel thinks of his film as a searing indictment of “the virus of religion” for its inconsistencies, hypocrisies, and violence. And he has no pretensions to fairness: but one proponent of faith, the former Bishop of New Jersey, gets an opportunity to make his case on film, and only, Samuel confides, to show that even rational people cling to ideas of the divine. For all the academic exposition, balanced debate is simply not on the agenda.

“Fuck that,” says Samuel. “I’m not going to balance anything at all. If you want balance, if you want the illusion of balance, you go to the conventional, you go to the state CBC and the other buffoons. Me, my documentary is presenting an attack on the idea of God.”

So be it. It’s certainly true that mainstream work on the subject prefers the dumbed-down and easily digestible to substance and controversy. Take, for instance, Barbara Walters’s 2005 piece “Heaven – What is it? How do we get there?” a hackneyed pastiche that reduces ideas to a collection of embroidered samplers. From this point of view, Atheism is a refreshingly deep, if unapologetically propagandistic, grapple with God.

Interviewees offering insightful colloquies include authors Tariq Ali (Clash of Fundamentalisms: Crusades, Jihads and Modernity) and Alison MacLeod (The Wave Theory of Angels), as well as Queen’s philosophy professor Christine Overall, among others. Although Samuel marshals practitioners of science, philosophy, and literature to make his case, the thrust of his engagement with atheism is undoubtedly political, focusing on the socially oppressive elements of religious belief and the horrors committed in its name. Thoughtful people will appreciate most of this analysis, but may roll their eyes when it doesn’t seem to fit. For instance, we get some vague musings on the chestnut without which no leftist oeuvre would be complete: the Israel-Palestine conflict. Although Samuel claims his film defies convention by critically tackling the Middle East, it falls short in its attempt to fully integrate Israel-Palestine into the discussion of atheism.

Samuel says he wanted to create a form that “goes down and sticks somewhere in the throat.” A few weeks after seeing the film, he hopes the audience will still be coughing up chunks for further inspection. To this end, some jarring images pepper the sanguine narrative, starting with the film’s title being splashed across the pages of a bible in black paint.

Based on the opening, I expected Atheism’s imagery to be full of shockers like, say, someone washing their armpits with holy water. Instead, it intersperses interviews with interpretive fare that sometimes complement the discussion, and sometimes regresses into corny computer-generated effects. And the visuals, like the interviews, remain limited to the Abrahamic religions, especially Christianity and Islam. Although Samuel says that a shoestring budget prevented him from branching out, the lack of attention to Eastern religions like Hinduism and Buddhism undermines the atheist challenge. To make his argument cut as deep as he wanted, Samuel should have tackled not only institutionalized religious practice, but spirituality more generally.

Although Atheism gives God a good run for his money, the film’s polemical style makes it unlikely to win converts among the devout. It exhorts its viewers against religion, yet still preaches a gospel. Like many sermons, it is alternately a little tedious, sometimes eyebrow raising, but thought provoking enough to make it worth sitting through.

Atheism will be screened at the Cinematheque Quebecoise (335 de Maisonneuve East) on February 16. For showtime and ticket information check cinematheque.qc.ca.

*

Cineaste Magazine, Fall 2007

Is God purely a projection of human hopes? Have the demands of Newtonian thinking and the Enlightenment severed our access to wonder? Or is the widespread acceptance of a simplified Big Bang theory a symptom of “nostalgia for divine creation,” as French astrophysicist Jean-Claude Pecker suggests? Julian Samuel tackles these questions in his documentary “Atheism,” a ponderous but nevertheless intriguing critique of contemporary monotheisms. Samuel’s visuals are bold and capricious, if occasionally unintelligible: the Old Testament supplies a canvas for his title images; the miracle of the loaves and fishes is illustrated with digitally multiplied footage of an angry shark and grilled chapattis; and Samuel’s hilarious analogue for the pressure cooker of political repression in the Middle East is an actual pressure cooker filled with Aloo Gobhi (cauliflower and potatoes). By contrast, the estimated “price tags” Samuel affixes to sacred art betray his unyielding derision for the religious establishment. While Samuel showcases a scientist, a philosopher, and experts on Islam and the Middle East as exemplary atheists and agnostics, the sole representative for monotheism is John Shelby Spong, a former Episcopal Bishop who excoriates the epistemological arrogance of atheism but is himself an enthusiast for Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s religionless Christianity. Toward the end of the film, however, Samuel takes an inspired detour into the expanding territories of Islamic and Christian fundamentalism, exposing how deep-seated commitments to religious fundamentalism give legitimacy to Middle East regimes and U.S. imperialism. This attention to the sway of politics over belief raises fascinating questions about our capacity to choose not to believe. As the Middle East expert Fadi Hammoud points out, at moments when human survival is at stake, “Sometimes you revert to god, sometimes you eat your god. (Distributed by Julian Samuel, juliansamuel@videotron.ca, telephone: 514 842 0884, www.juliansamuel.net – Michelle Robinson.

*

“Québec athee,” Claude M. J. Braun

(Les éditions Michel Brulé, 2010)

“Le dernier film québécois à traiter de l’athéisme est présenté par le réalisateur au public, lors d’interviews, de façon tordue, presque hypocrite, probablement sardonique. En l’occurrence, le jeune réalisateur montréalais, Julian Samuel décrit l’intention de son film documentaire Atheism (2006) comme étant une explication de « comment un athée, comme moi devient religieux ». Mais en réalité, ce qui est livré est le contraire, et deux fois plutôt qu’une. Car le film penche fortement vers l’athéisme, et ne laisse que très peu d’oxygène à la religion qui n’est représentée que par un seul protagoniste parmi de nombreux athées : un chrétien avec une vision castratrice de sa propre croyance. Le film est une série d’entrevues avec des savants et intellectuels de haut niveau. Le documentaire nous plonge rapidement dans les réflexions et positions émanant des interrogés. Cette démarche produit un remarquable tableau de divers ancrages religieux : les croisades, les guerres, l’inquisition et le mystère. Par opposition, elles sont suivies par d’intéressantes interrogations d’ordre scientifique et philosophique du réel. À travers des interviews, Julian Samuel sonde subtilement les sensibilités de ses interlocuteurs pour ensuite les confronter avec les siennes, qui relèvent d’un athéisme abouti. Ce qui empêche le film de nous plonger dans l’aridité de l’intellectualisme verbeux est l’imagerie iconoclaste et allégorique, l’exploitation de caligraphies et de gestuelles saisissantes, d’icônes évocateurs, d’images judicieusement choisies, qui renforcent les propos. L’humour est aussi au rendez-vous et les propos sont mordants. Le point de vue religieux n’a aucune chance dans ce film d’atteindre quelque crédibilité. Par contre, le film illustre comment les thèmes religieux, aussi fascinants soient-ils dans le cadre religieux, le sont encore plus dans les cadres scientifique et philosophique.”