The Library in Crisis, 2002; 46:41 minutes

The Library in Crisis is a documentary on libraries; historic and contemporary bibliocides; literacy and the French Revolution; libraries morphing into centers of E-commerce; the impact of copyright and the digitization of texts; the Khmer Rouge’s catalogues of people killed; and the World Trade Organization’s concern for democracy.

*

The Library in Crisis, 2002

Press Release

Introduction by Vinita Ramani

The Library in Crisis (46 minutes, 2002) is a documentary on libraries; historic and contemporary bibliocides; literacy and the French Revolution; libraries morphing into centers of E-commerce; the impact of copyright and the digitization of texts; the Khmer Rouge’s catalogues of people killed; and the World Trade Organization’s concern for democracy.

The interviewees are:

Brian Campbell, Past-chair, Canadian Library Association Information Policy Committee and Founding President, Vancouver Community Network

Donald Gutstein, Senior Lecturer, Communication, Simon Fraser University (author, “E.Con, How the Internet Undermines Democracy”.

Fred Lerner, author “The Story of Libraries, From the Invention of Writing to the Computer Age”

Ian McLachlan, Chair of Cultural Studies, Trent University

Manal Stamboulie, Head Librarian, Lakefield College School

Martin Dowding, Assistant Professor, School of Library, Archival, and Information Studies, University of British Columbia

Peter F. McNally, Professor, Graduate School of Library and Information Studies, McGill University

Sumaiya Hamdani, Islamic Historian, George Mason University

*

Film-maker and writer Julian Samuel has made a four-hour documentary on Orientalism and has published a novel, Passage to Lahore, [De Lahore à Montréal]. You may contact him at

*

Sites:

http://www.ccca.ca/artists/artist_info.html?languagePref=en&link_id=1813&artist=Julian+Samuel

http://www.colorado.edu/journals/standards/V7N2/ARTS/samuel.html

http://www.colorado.edu/journals/standards/V7N1/ARTS/arts.html

http://www.colorado.edu/journals/standards/V7N1/ARTS/samuel1.html

http://www.web.net/blackrosebooks/iem.htm

A commentary on The Library in Crisis

by Vinita Ramani, curator, Singapore International Film Festival, April 2002

In the recent past there has been much furor surrounding the meetings of institutions such as the World Trade Organization (WTO) Free Trade Area of the Americas (FTAA) or North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). The corresponding clout of protestors has been aided by the ubiquitous presence of the Internet, which has acted as a useful tool in decentralized cooperative organization. So much attention has fallen upon this medium of communication and information acquisition, that little has been said about how its predecessor and still existing sibling – the library – figures into the larger equation. Filmmaker, writer and visual artist Julian Samuel has undertaken the project of tracing the birth and current trajectory of this public service institution par excellence. ‘The Library in Crisis’ follows ‘The Raft of the Medusa; Into the European Mirror; and City of the Dead and World Exhibitions (1993 -1995). The trilogy largely concerned itself with the nuances of colonialism and imperialism, bringing the articulations of history into the realm of documentary filmmaking. Since the library is the institution in question here, the concern with history has not been abandoned. In a recent interview, noted writer and filmmaker Tariq Ali observed that it is as if history has increasingly become too subversive because the past has too much knowledge embedded in it. How historiography has shifted over time can be aptly charted by following the progress and function of writing and libraries. This is the core articulation of the documentary.

The video consists of interviews with eight academics, historians, and librarians who offer a kind of collective genealogy of the library, from the advent of writing and universities to its use as a tool for disseminating information by the state. This is connected to present concerns regarding the digitization of texts, copyright laws and how the privatization of a public domain amounts to an infringement on civil liberties. As Donald Gutstein aptly notes in the film, the library is in many ways the foundation of a democratic society. The full gravity of this statement is articulated as the documentary moves towards considering bibliocide – euphemistically described as “de-accessioning” books.

Tracing the beginnings of writing, Fred Lerner and Ian McLachlan note how it oscillated between several roles, with the information function and wisdom embodiment function of writing often caught in a proverbial tussle. This tension between contradictory forces manifests most pointedly in the shape of the library as an institution that served both purposes. Depending on the nature of the historical context, the roles played by libraries varied considerably. Samuel uses understated juxtapositions to convey this tension through the documentary. The images are not always inter-cut with each other, thereby occupying full screen presence. Instead, he repeats his preference for split screens, previously utilized in his trilogy. The camera roves across the spines of aged books on shelves, while one of the interviewees speaks in a smaller frame – a screen within a screen. Similarly, pages awash in sepia-toned light share space with flashes of computer screens where a search for Nalanda University yields a digital image of the building. Thus attention is constantly drawn to the contrast between fragments of digitized information with their immediacy, and the organization of texts, which necessarily require more time and patience.

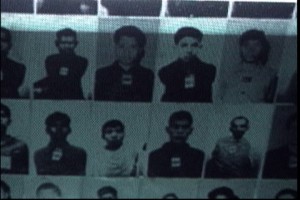

Islamic historian Sumaiya Hamdani offers an important critical perspective on libraries as purveyors of information dissemination. There is particular relevance to her observation that the Industrial Revolution and the rise of the nation state required an invented homogeneity. This was embodied in education, libraries and state propaganda. The alignment of education and libraries with state propaganda is one shift in the interpretation of libraries that is astutely explored. No surprise then, that Peter McNally refers to the underground network of publications written during the French Revolution. Rather than censorship, a more effective means of suppressing dissent was provided by creating middle-class values of morality through mass literacy. This point is visually complemented by website images of Khmer Rouge victims, perhaps hinting at the point that creating a mass culture also allowed for the elimination of a nameless mass. Libraries therefore, were increasingly used as repositories of detailed information on genocide, and the propagation of state ideology.

Manal Stamboulie, Donald Gutstein and Brian Campbell further the multiple interpretations of libraries presented in the documentary by highlighting how they have now become centers of E-commerce. The inclusion of software into the copyright act in 1976 has raised crucial questions about corporate take-over of information. While efforts are being made to copyright and commodify information, libraries increasingly become the carriers of electronic information – in itself incomplete and frequently less widely accessible than one presumes. Much of the fuss around information technology has revolved around issues of availability and the curtailment of file sharing and free access. However, Gutstein’s point that institutions in the information technology field are more concerned with how to charge for information rather than how to increase access acts as an important connective to previous definitions of libraries. What was previously a public service now faces infringements from the private sector and institutions such as the World Trade Organization play a role as participants in support of this corporate orientation. Thankfully, Samuel avoids any conclusive remarks about these dramatic shifts. The threat to free access and the marginalization of a library’s role in questioning and creating ideas are assertively put forward. But the various perspectives avoid being prescriptive, therefore allowing room for debate.

Overall, the questions considered in this documentary have wide applicability inside and outside classrooms. Its considerations of how writing and ideas have developed through time make it a relevant tool in fields such as history, cultural theory and media studies, especially if one considers the library as a core institution within the academy. Perhaps more significantly, it handles the phenomena of globalization without stating the obvious or re-playing the now-popular trope of protestors who constitute the “anti-globalization” movement – itself an inaccurate summing up of a diverse movement. Rather, by delving into the historically shifting function of libraries and current developments involving corporate presence, it draws attention to how globalization concretely threatens intellectual freedom as well as political and economic liberties. By raising the idea of a library as a community whose reading rooms provide presence, distance and a space to engage in debates, it implicitly compels us to question how we understand the growing presence of web-based communities and what limits will be imposed upon this method of social activism.

*

Vinita Ramani interviews Julian Samuel, a Montreal film-maker and writer.

http://www.filmfest.org.sg/pr.htm

Vinita Ramani: The first thing that comes to mind watching ‘The Library in Crisis’ is a quote by Tariq Ali in an interview he did soon after September 11th. He said, “…. the one discipline both the official and unofficial cultures have united in casting aside has been history. It’s somehow as if history has become too subversive. The past has too much knowledge embedded in it, and herefore it’s best to forget it and start anew.” Has history always been of topical concern to you in your work and how does that relate to what is happening with libraries?

Julian Samuel: I am not a historian nor am I an analyst of contemporary world affairs. I am, however, a documentary film-maker who has a fundamental grasp on what it means to expose audiences to extensive discussions of a historical nature. Will my works bring about a skepticism that will empower us to make for a better world? What a dreamer some of your readers might say. I believe that it is only via a discussion of historical issues that we will be a able to understand and act in the contemporary world. For example, Noam Chomsky has consistently referred to recent Middle-East history in order to expose the current-day slaughter of Palestinians. By the way, the Israelis are directly responsible for the poor condition of libraries in Palestine (66th IFLA Council and General Conference Jerusalem, Israel, 13-18 August by Erling Bergan, Bibliotekarforbundet, Orslo, Norway; web site for his essay: http://www.ifla.org/IV/ifla66/papers/170-172e.htm).

And on the subject of history – well let’s see what kind of future this area of study has. For years now, schools in France have not given the failed Paris Commune of 1871 the attention it deserves. The Franco-Prussian war of 1870-71 and the consequent siege of Paris lead to the one of first experiments in social democracy. It must be difficult to study history in societies which specialize in communal violence such as India, Pakistan and Canada a country which has a history of violence against First Nations, et al., ad nauseam. Depending on the country, the repercussions from the history class room to the street are immediate, and the elites will try to exert – as they have always done – limiting parameters on the teaching of this subject as well as others. Absurdly, there are news reports that tell of a move toward controlling actually who studies biology. Will students with “Middle-Eastern” features be observed, controlled and discouraged from advancing in this field? One wonders.

VR: You do not merely address the issue of the threat of privatization of what is essentially a public service in your documentary. You specifically use the word “bibliocide” to describe the phenomena. What was the intention behind that usage and how widespread a phenomena is it?

JS: Ian McLachlan, one of the main interviewees in The Library in Crisis, uses this word. Biblocide is happening as we speak. The forthcoming part of this documentary on libraries and information in society, entitled, “From Alexandria to Cyberspace: The Library in Crisis” will address the following themes: permanent book burning – the enlightened destruction of primary documents in the libraries of western democracy; the future of the study of history based on primary sources; commentaries and images from the developing world. What am I basing my suspicions on? Nicholson Baker has a written a brilliant work of humanist scholarship, “Double Fold, Libraries and the Assault on Paper” (2001). He makes the following claims:

– That major librarians at Library of Congress, Yale, Harvard, et al., have since the last 40 or so years microfilmed newspapers and books, subsequently discarding, selling or destroying the originals. The process of microfilming requires that books have to be disbound (the binding slashed open with a knife) because the pages have to be put perfectly flat on a table in preparation for photography.

– That there is a attempt on the part of major libraries to transfer books to the digital world. Once the books have been filmed or scanned, they are not re-shelved, but sold or “pulped”.

– Librarians need more and more bookshelf space; space means the expenditure of money which is not easily available. Yet, year after year more and more books and newspapers are published. Librarians of major collections say the only way they can make more space is to microfilm the old documents, throwing them away afterwards. The Library of Congress leads the way in this book and newspaper massacre.

– Microfilming indirectly results in the destruction of books and newspapers. Microfilm cannot work as a substitute for paper; many microfilms of newspaper are incomplete, issues and pages missing, badly cropped pages, missing texts. Nicholson Baker estimates, conservatively, that one million books and tons of newspapers have been intentionally destroyed. Furthermore, microfilm is not as stable as paper.

– Various conservation processes, including the use of diethyl zinc (an explosive element found in fuel-air bombs), have not saved books from acidity, but rather have ruined and in some cases destroyed them. Preservation is destruction: “Just leave the books alone.”

– Filming and scanning of old books and papers is much more expensive than simply building a large off-site warehouse. It is exponentially more expensive to store complete books on hard disks that to build warehouses.

Baker objectively concludes that the destruction of books has been utterly unnecessary: American libraries have tossed out 975, 000 books worth $39 millions dollars, and have no intention of stopping.

VR: Part of the process of privatizing public services reveals a tussle between what may be termed “knowledge” as opposed to “information”. A recent article points out the emergence of companies launching “information markets” which would provide reference service for paying customers and

would call themselves “library-like services” in order to claim government funding. In light of this, what are your thoughts on the digitization of texts and the prevalence of the Internet as a resource? What impact is digitization having on libraries?

JS: I haven’t the expertise to respond to these questions. However, let me offer the following:

1) Are you suggesting that “digitization” may become “privatization”? Perhaps. Privatization will mean that libraries may charge for knowledge. If we as a public don’t resist the primrose path toward privatization of knowledge, the full-steam ahead privatization of education (what the Tony Blair is trying to do in the UK), privatization of health care we are doomed. People should make their will known to the politicians who claim to represent us in parliament and city councils: their feet must be held close to the fire otherwise their natural proclivity to falsely represent our interests will prevail; these thinkers and plotters are committed to making more money, not extending democracy. They want to project their ugly policies from above without listening to anyone. Rancid cliché: hello: the rich are not interested in solving the problems that follow from globalization.

VR: The threat posed to libraries, and the de-accessioning of texts (a term Ian MacLachlan cites in the film to point out how books are “cancelled”, or taken off the shelves) extends to universities as well. In a sense, the definition of a university as a place for intellectual debate and exchange

itself is being de-accessioned. Is there a broader agenda motivating this other than the workings of privatization?

JS: Books need not be “deaccessioned.” It is cheaper to build large warehouses with roofs that do not leak rather than rip apart books for filming – film lasts for only a few decades. Books last for ages – longer that computers stay cutting edge.

Privatizing information means that it becomes easier for the elites to control who gets to see information (and documents). At the moment, it is getting harder and harder to look at archival government documents in the USA – rumour has it that the US government may even put a back curtain around the beautiful Statue of Liberty. The post 11 September Bush administration is particularly worrying. Julian Borger, a journalist for the Guardian Weekly, explicitly addresses the issue of the 1966 Freedom of Information Act and the current access to government documents (Thursday March 7, 2002).

5) The term “globalization” is tossed around liberally and inversely, the term “anti-globalization” is used to dismiss any serious (and not always supportive) concern for the policies that fall under this ambiguous term. In a sense, it even feels like a ruse designed to detract attention from the various issues that fall within its realm. How does your film grapple with this term?

JS: The term “globalization” means privatizing everything from libraries to health care (I realize that not all countries have public healthcare) and even privatizing the process of privatizing itself – this process has produced a litigious culture the likes of which we have never seen. Microsoft.

“The Library in Crisis” tries to put historical events such as the fall of the library at Nilanda and the contemporary digitization of texts in a framework which allows us to make comparisons and to act in an informed way. Without some knowledge of the past we can’t act.

6) Your previous work on Orientalism, (The Raft of the Medusa; Into the European Mirror; City of the Dead and The World Exhibitions) consisted of three documentaries that examined colonialism, imperialism and how historiography operates, amongst other issues. Is there a similar series in the works built around the thematic concerns raised in ‘The Library in Crisis’?

JS: In a very general sense, “The Library in Crisis” is similar to my work on how the Middle East and parts of Asia are configured within the workings of western imagination. “The Library in Crisis” focuses all interviews onto one single site: the library. This public institution is one source for the preservation and further development of democracy.

However, there is a ugly trend afloat: charging for library cards. This trend has not yet hit Montreal, but the province of Alberta is now charging for library cards, and Montreal area libraries are charging for borrowing best sellers – about five bucks a shot – total fraud this is. We have *already paid* for the library and *all* its contents – the shelves, the books, the networks, the data bases, the journals, the newspapers, the tables, the CDs, the old LPs, the 45s, the chairs, the air-conditioning, the heating *through our tax* contributions. Why are some odious and conformist library administrators starting to *double charge* us? A simple petition by library users could stop this hideous trend toward barring those who may not be able to afford to use the library. Without the public library we are dead and finished as a civilization. Protest and survive is the that the answer? I am not sure.

*

Library Journal, January 2003

Centuries of History in Minutes

The Library in Crisis. colour. 46 mins. Julian Samuel, Film-maker Library, 124 E. 40th Street, New York, NY 10016; 212 808-4980; www.filmakers.com 2002. $295 (Rental: $75). Public performance.

In this brisk, interesting documentary, producer Samuel, a Canadian film-maker (Red Star Over the Western Press), author (Into The European Mirror), and artist, traces the history of civilization through the idea of the library, all in 46 minutes. Chock-full of commentaries from noted scholars, including Fred Lerner (The Story of Libraries), Peter McNally (McGill Univ.), and Donald Gutstein (Simon Frazer Uinv.), the smartly styled production covers key stages in writing, printing, publishing, and, woven throughout, library development. Beginning with prehistoric times, the video discusses the ancient Chinese use of libraries, initial writing by bureaucrats and religious clerics, the Enlightenment, the printing press, the beginnings of universities, and the impact of the Industrial Revolution and the rise of the nation-state on the growth of literacy. The speakers also review the influence of the underground press during the Age of Revolution and the invention around 1850 of the concept of the free public library and free public schooling. Appearing at the end of what starts out as a fact-based thumbnail history are today’s hot topics in the library community (“the library in crisis”): copyright protection, the growing trend toward the commercialization of information and the privatization of libraries, and privacy concerns regarding patron records. The subjects covered are numerous, and the pace is quick, although the obviously highly personal viewpoint regarding the World Trade Organization is, at best, naïve. The lack of any introduction, or summary of main points (the film just begins and end) may force a preliminary setup by instructors in order to help viewers better connect these varied comments to current conditions. Recommended for all MLIS students and libraries supporting MLIS curriculum. – Dale Farris, Groves, TX

*

Randy Pitman

Publisher/Editor

Video Librarian

Seabeck, WA

The Library in Crisis **1/2

(2002) 46 min. $295. Filmakers Library. PPR. Color cover.

An ancient king once consulted a keeper of the books to find a proper and efficient curse to lay on an enemy (possibly one of the first reference questions!). Born out of the need to preserve bureaucratic edicts, libraries continue to serve an essential function in human history as a repository for the cumulative store of human knowledge and culture.

Producer Julian Samuel’s The Library in Crisis offers a rather disjointed review of the historical role of libraries, while raising questions about the function of libraries in the future. Scholars recap notable events–from the invention of paper and rise of the printing press, to the appearance of 19th century visionaries such as Andrew Carnegie, who promoted the glorious but also somewhat subversive idea of free information for the masses–in the evolution of libraries, before examining how computers offer both opportunities and challenges to the contemporary library. One librarian notes that, information-wise, the Internet is “thin” compared to the resources available in print, yet computers have also opened the door for competition to the library, as new businesses commercialize, privatize, and restrict information. While the program asks provocative questions, they are not seriously addressed within the hour-shy running time (in fact, the librarian’s role as gatekeeper and guide to this world of knowledge is almost completely ignored, making librarians second-class players in their own story). Given the fact that this is a Canadian production, academic libraries in Canada should consider, but most U.S. libraries will want to wait for a broader treatment of the topic. Optional. Aud: C, P. (S. Rees)

*

3 février 2002 – COMMUNIQUÉ DE PRESSE

(English follows)

Provenant des réalisateurs Julian Samuel et Mary Ellen Davis

Le documentaire “The Library in Crisis”, réalisé par Julian Samuel a été

sélectionné pour le Singapore International Film Festival mais rejeté

par un jury composé de blancs pour Les Rendez-vous du cinéma québécois

(15 au 24 février 2002). “The Library in Crisis” répond pourtant à

plusieurs critères d’éligibilité: “oeuvres qui ont su traduire, à partir

d’un point de vue original et pertinent, une sensibilité intellectuelle

et esthétique, (…) oeuvres indépendantes n’ayant pu bénéficier d’une

diffusion adéquate, (…) oeuvres atypiques, etc.”

Mary Ellen Davis retire son documentaire “Le Pays hanté” des Rendez-vous

de cinéma québécois en solidarité avec Julian Samuel. Ce documentaire (à

l’affiche du Cinéma Parallèle Excentris, janvier 2002) a gagné un prix

en Équateur remis par l’organisation autochtone CONAIE, mais a été

refusé par Radio-Canada/CBC, Télé-Québec, Rencontres internationales du

documentaire de Montréal, Images du Nouveau Monde (Québec).

Bien entendu, le fait que Les Rendez-vous du cinéma québécois présentent

quelques oeuvres de réalisateurs de minorités visibles peut atténuer une

responsabilité en termes de discrimination. Pourtant, depuis ses 20 ans

d’existence, aucun individu provenant de minorités visibles anglophones

n’a occupé un poste décisionnel dans le cadre du festival. La directrice

et le personnel-clé sont des francophones blancs. Sur la base de

contribuables montréalais, plus de 18% ne sont ni blancs ni

francophones, pourtant les minorités visibles sont exclues des fonctions

décisionnelles aux Rendez-vous du cinéma québécois.

Nous sommes convaincus que nos oeuvres auront de meilleures chances de

diffusion et de reconnaissance si les comités de sélection, les jurys et

toutes les institutions incluent des minorités visibles dont la langue

maternelle ou d’adoption est le français ou l’anglais.

Julian Samuel

Mary Ellen Davis

*

The Library in Crisis (46 minutes, 2002) est un documentaire sur les

bibliothèques; les bibliocides du passé et du présent; le niveau

d’alphabétisation et la Révolution française; la transfiguration des

bibliothèques en centres commerciaux cybernétiques; l’impact du droit

d’auteur et de la numérisation des textes; les archives des Khmers

Rouges; les préoccupations de l’Organisation mondiale du commerce en ce

qui concerne la démocratie.

*

Nous vous invitons à communiquer avec la directrice des RVCQ

c.c. MP Marie Malavoy, PQ, co-présidente d’un comité bilatéral

franco-québécois sur la diversité culturelle

c.c. des réalisateurs indépendants ici et à l’étranger

* * *

3 février 2002 – PRESS RELEASE

From: Film-makers Julian Samuel and Mary Ellen Davis

Julian Samuel’s documentary “The Library in Crisis” has been accepted at

Singapore International Film Festival but rejected by an all-white jury

at Les Rendez-vous du cinéma québécois (15-24 February, 2002). “The

Library in Crisis” reflects several of the eligibility criteria:

“oeuvres qui ont su traduire, à partir d’un point de vue original et

pertinent, une sensibilité intellectuelle et esthétique, (…) oeuvres

indépendantes n’ayant pu bénéficier d’une diffusion adéquate, (…)

oeuvres atypiques, etc.”

Mary Ellen Davis has retracted her documentary “Haunted Land” from Les

Rendez-vous de cinéma québécois in solidarity with Julian Samuel. Her

documentary (released at Cinéma Parallèle Excentris in January, 2002)

won an award from Ecuador’s First Peoples’ organization CONAIE, but has

been rejected by CBC/Radio-Canada, Télé-Québec, Rencontres

internationales du documentaire de Montréal, Images du Nouveau Monde

(Québec).

Of course, the fact that Les Rendez-vous du cinéma québécois will screen

the works of a few visible minority film-makers may mitigate the charge

of discrimination. However, since its inception 20 years ago, not a

single anglophone visible minority has ever been hired for a key

decision-making position within this festival. The director and all

personnel in key positions are white francophones. The tax base in

Montreal’s population is over 18 per cent non-white and non-francophone,

yet visible minorities are excluded from decision-making positions at

Les Rendez-vous du cinéma québécois.

We are convinced that works such as ours will stand a better chance for

more visibility and acknowledgment if selection committees, juries and

all institutions include visible minorities, both French and

English-speaking.

Julian Samuel,

Mary Ellen Davis

*

The Library in Crisis (46 minutes, 2002) is a documentary on libraries;

historic and contemporary bibliocides; literacy and the French

Revolution; libraries morphing into centers of E-commerce; the impact of

copyright and the digitization of texts; the Khmer Rouge’s catalogues of

people killed; and the World Trade Organization’s concern for democracy.

*

We urge you to contact RCVQ director, Ségolène Roederer:

c.c. PQ MP Marie Malavoy, co-president of a joint committee with France

on cultural diversity

c.c. independent filmmakers throughout the world

*

Filmmaker pulls work from Quebec festival

By MATTHEW HAYS

Special to The Globe and Mail

Friday, February 1, 2002 – Print Edition, Page R7

MONTREAL – A filmmaker has pulled her selection from the prestigious 20th

Les Rendez-vous du cinéma québécois in solidarity with another filmmaker

whose says his work was not chosen for the festival because of racism.

Mary Ellen Davis yanked Haunted Land, a documentary about genocide in

Guatemala, this week, saying fellow documentary filmmaker Julian Samuel had

been unfairly omitted from the screenings of Quebec cinema, which run Feb.

15-24.

Samuel, who is Pakistani-Canadian, says the decision not to accept his film

smacks of racism and discrimination on the basis of his being anglophone.

His film, The Library in Crisis, is a 43-minute academic examination of the

history and decline of the institution of the library, and the effects of

its descent on democracy itself.

Representatives of Les Rendez-vous, an annual roundup of the province’s

cinema that showcases much of the year’s cultural product, acknowledge

Samuel’s film was not accepted, but say his minority status had nothing to

do with the decision. Adrian Gonzalez, a spokesman for Les Rendez-vous,

points out that, while all feature-length narrative films submitted

automatically screen at Les Rendez-vous, documentaries and animated films do

go through a jury selection process. Of 85 documentaries submitted, Gonzalez

reports, only 50 were accepted. “We only have about 10 days for the event,”

he says. “You send your film in, it doesn’t mean we’re going to show it. We

can’t possibly show everything.” As well, Gonzalez says that a number of

filmmakers of non-white lineage have had their projects accepted into the

festival, including celebrated performance artist Atif Siddiqui and noted

documentarian Tahani Rached. More specifically, Gonzalez says the

documentary jury found Samuel’s film “boring.”

While Samuel says he doesn’t think the individuals involved with Les

Rendez-vous are racist per se (“I’m sure they’re nice people”), he does say

that it suffers from a systemic condition that’s endemic to many Quebec

cultural institutions. “There simply aren’t enough non-white or anglophone

representation here,” he insists, pointing out that in its 20-year history,

Les Rendez-vous has never had a non-white anglophone in any of its key

positions. “They should be proud of the minorities in this province. These

key decisions are being made without our input. They’re using our tax money

to exclude us. They should be made to share the resources.”

As for the charge that his film is boring, Samuel responds, “I’ll accept

that. Perhaps they didn’t understand the film. My understanding is that they

only watched part of it. The film has been accepted to the Singapore Film

Festival in April. It’s sad to me that the film would get accepted there and

receives such caustic rejection here at home.”

While acknowledging that Samuel can be a bit aggressive in his stances,

filmmaker Davis agrees with him in principle and says that were more visible

minorities included in the selection process at Les Rendez-vous, his film

would have stood a better chance. “It makes sense that he would ask for

this. Diversity would definitely have a positive effect on the process.

Committees can make the decisions they want, granted, but they will have a

different sensibility if they include more than just white francophones.”

Les Rendez-vous brass stand behind their decision. Segolene Roederer,

director of the festival, says race played no part in the decision. “Some

very white people have been rejected, as well as some very famous white

people. What can I say? We get calls from white people who are disappointed

too. Last year, Samuel confronted me about his work not getting screened at

the event. But when I asked him if he’d submitted it, he admitted he never

had. Now he has, and he’s upset because he’s not been accepted.”

As to the issue of diversity, Roederer says, “Finding visible minorities to

serve on the committees is part of my mandate, for sure. It’s something

we’re working towards.”

“There are 100 other festivals for Samuel to submit his film to,” Gonzalez

adds. “He’s acting like a little kid who gets angry because they didn’t get

a toy for Christmas.”

Copyright © 2002 Bell Globemedia Interactive Inc. All Rights Reserved.

*

Mirror, 31 January 6 February, 2002

A racist Rendez-vous?

by MATTHEW HAYS

Chronically disgruntled filmmaker Julian Samuel is at it again. Last year,

he complained loudly to the director of Les Rendez-vous du cinéma québécois

about the fact that his film wasn’t being shown at the event. Then in her

first year running the festival, which showcases most of Quebec’s film

productions from the previous year, Segolene Roederer responded in a

straightforward manner. “If you wanted to be considered for Les

Rendez-vous,” she told him, “perhaps you should have actually submitted

your film in the first place.” (Apparently Samuel had forgotten that you’re

supposed to actually send your movie in.)

So Samuel did just that. This year, he submitted his latest, titled The

Library in Crisis, a 43-minute documentary about the threat to democracy

posed by our declining libraries. A number of academic thinkers on the

subject are interviewed. (Though the plot may sound familiar, careful not to

confuse this film with the latest Schwarzenegger vehicle.) Anyway, the folks

over at Les Rendez-vous, which runs from Feb. 15-24 and is celebrating its

20th anniversary this year, had their own label for the film: Boring. It

seems they were less than thrilled with The Library in Crisis, and thus are

not screening it.

Samuel says they’re open to their own opinions, but points out that the

committees for film acceptance at Les Rendez-vous are lily white, and have

been for far, far too long. The people who run Les Rendez-vous, he argues,

are all pleasant enough as individuals, but adds that were there greater

minority representation his film would probably have stood a better chance.

Adding fuel to his fire is the fact that his film has been accepted at the

Singapore Film Fest, which takes place in April.

Les Rendez-vous brass are sticking to their guns. They’re working on the

diversity thing, they say, and point to a number of minority-status

filmmakers whose work is gracing their showcase, including Pepita Ferrari,

Yuti Sewraj and Carlos Ferrand. In a stunning blow to the event, however,

Mary Ellen Davis has pulled her film, Haunted Land (now screening at the

Ex-Centris in French-subtitled version), from Les Rendez-vous in solidarity

with Samuel. Davis argues Les Rendez-vous should definitely be opening up

its juries and recruiting more minorities to serve on their committees.

Those wishing to chime in on this controversy can e-mail Les Rendez-vous.

CineGael, that most excellent Irish film fest, is having a mini-festival of

women’s films this weekend. Included in the series are Bent Out of Shape,

Blessed Fruit, Silent Grace, Hoodwinked, Nora, Twelve Days in July and

Hush-a-bye Baby (director Margo Harkin will be present at the screenings of

her films, Twelve Days and Hush-a-bye). See www.cinegale.com for more info.

The Genies, Canada’s own movie awards, air this Thursday, Feb. 7 on CBC. A

simple prediction, but a fairly safe one to make: Call me Jojo and stroke my

crystal ball, I suspect Atanarjuat, the stunning Inuit epic, will sweep. :

COMMENTS:

CBC radio interview: 5 February 2002, copy on cassette

*

What’s a film festival without a controversy?

Is the Rendez-Vous du Cinema Quebecois racist? Yes, says one film-maker whose film was rejected. Nonsense, organizers reply, citing the event’s diverse lineup.

JOHN GRIFFIN, Montreal Gazette, 6 February 2002

The Rendez-Vous du Cinema Quebecois celebrated its 20th birthday at the Cinematheque Quebecoise yesterday with a press.. conference, a late-morning cocktail and a controversy. The 20th annual look back at the previous year in film and video production chez nous will screen 187 works at five Montreal locations between Friday Feb. 15, and Sunday. Feb. 24. One of those * films will not be Julian Samuel’s The Library in Crisis. Another will not be Mary Ellen Davis’s Pays Hante (Haunted Land). Davis has withdrawn her film from this year’s Rendez-Vous in support of fellow Montreal director Samuel, who says his documentary was rejected by the selection committee because of racism. Samuel is Pakistani-Canadian. “The entire cultural apparatus in Quebec is flagrantly racist,” he said yesterday. For instance, the Rendez-Vous has never had a single visible minority in a key decision-making position, he said. While improvements have been made in the selection, “it’s time to take the next step,” Samuel said. “Minorities need to get inside the apparatus.” Festival director Segolene Roederer said Samuel’s film wasn’t the.. only work rejected for the documentary section. “Forty others weren’t accepted either. In the end we chose the films we think are best. His wasn’t right for this event.” Roederer also recalled that Samuel was “very aggressive in accusing us last year of not showing his film. When pressed he admitted he hadn’t submitted it.” Davis’s documentary, about genocide in Guatemala, was to be one of 40 being shown. “It’s nice to be accepted,” she said. “But we still have to evolve. We need minority presence at the selection level. This gesture is trying to send that message.” Festival communications director Adrian Gonzalez is fed up with what he considers a tempest in a teapot. Twelve of the documentary selections are from minorities, he noted yesterday. “When you enter a film in a festival, you never know what’s going to happen. Professionals accept a jury decision.” Gonzalez is gay, Latino and a salaried employee… At one time, the Rendez-Vous did not accept English-language films. This year, 29 features, shorts, documentaries and experimental works are in English or – more accurately reflecting the reality of today’s Quebec – a mixture of French and English.

John Griffin

Coming soon The Rendez-Vous du Cinema Quebecois begins Friday, Feb. 15, and continues through Sunday, Feb. 24. Tickets go on sale next Tuesday at the Cinematheque Quebecoise, 335 de Maisonneuve Blvd. E., and the National Film Board Cinema, 1564 St. Denis St. The Web address is www.rvcq.com.

*

support letters:

Dear Segolene Roederer:

i am writing on behalf of a number of people from the British

film-making community who are shocked and saddened by the news of the

withdrawal of Julian Samuel’s film from your festival.As an

internationally renowned artist,journalist,novelist and

film-maker,Julian Samuel’s work has been for many years at the

forefront of our collective quest for a cinema of

Difference,Diversity and Multiculturalism.Recent world events make

such a cinema even more relevant, timely and desireable.We believe in

the continuing existence of this cinema and we also believe cannot

grow without nurturing, support and exposure. It is therefore in this

spirit that we view with some alarm your decision effectively censor

the showing Julian Samuel’s new film.

SIGNED

John Akomfrah

Lina Gopaul

David Lawson

Edward George

Anjalik Sager

Kodwo Eshun

Adam Kossoff

Lucia Ashmore

*

14 February 2002

Madame Ségolène et le Comité de sélection des RVCQ,

J’ai pris connaissance du communiqué de presse émis par Julian Samuel et Mary Ellen Davis pour protester contre la non-inclusion du documentaire de M. Samuel, “The Library in Crisis.” Je ne sais pas si le fait de n’avoir pas accepté le documentaire s’explique par de la discrimination de la part des RCVQ. Mais il/elle soulèvent un point intéressant en notant que les postes décisionnels de cadre des RVCQ soient occupés par des personnes de couleur blanche uniquement. Je suis d’accord avec eux que vous devriez ouvrir des postes décisionnels à des “non-blancs/blanches” lors des prochains RVCQ, question d’apporter de l’équité ainsi qu’un reflet d’abord de la réalité dans le domaine du cinéma québécois et, comme il/elle l’ont mentionné, de la réalité démographique de Montréal.

Mais, aussi important à mon avis est le fait que les Rendez-vous du cinéma québécois aient abdiqué à une responsabilité de diffuser de l’information cruciale fournie par un cinéaste qui pose un regard critique sur ce qui se passe réellement dans notre monde. Je suis bibliothécaire et je sais pertinemment que le système des bibliothèques publiques et universitaires sera sous attaque lorsque les institutions comme l’Organisme mondial du commerce (et surtout l’entente connu sous le nom du GATS – General Agreement on Trades and Services) concluent les ententes de commerce international qui sont en négociation actuellement (voir un article à ce

sujet au: http://libr.org/ISC/articles/14-Hunt.html). Ce phénomène fait partie des changements majeurs en train de s’opérer dans le commerce international qui donneront un pouvoir incroyable aux entreprises au détriment des droits des citoyennes et citoyens de tous les pays. Je ne sais pas si Julian Samuel traite du sujet des bibliothèques adéquatement (j’aimerais pouvoir voir son film pour pouvoir en juger moi-même), mais, selon la description de son documentaire, il aborde des questions importantes à ce sujet. Puisque les médias traditionnels ne traitent pas du tout de ces questions et sachant que beaucoup de gens ont soif d’information pour pouvoir alimenter leurs luttes contre la mondialisation, je réitère qu’il incombe aux événements tels que les Rendez-vous du cinéma québécois d’assurer la diffusion de documentaires de penseurs critiques qui nous informent sur la réalité mondiale.

Vous avez beaucoup de courts métrages classés art et expérimentation ou fiction dans votre programme de cette année; personnellement, je préfèrerais voir beaucoup plus de documentaires qui fournissent de l’information et de la réflexion.

Merci de votre attention.

Colette Lebeuf

*